| You may have learned to think, but how do you know that you are doing more than rearranging your prejudices? Formal cognitive distortions are about learning how to think about thinking itself. You are asking yourself, “Does this thought make sense? How do I know?”

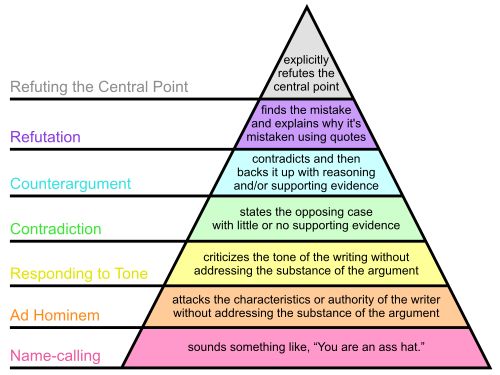

Humans have created an amazing number of ways to lie to themselves and deceive others. The result is that we do not think straight and so block ourselves and our societies from waking up and growing up. That keeps us as individuals and collectives from achieving and maintaining balance or from accessing meaningful, lasting, positive transformation. Understanding formal cognitive distortions is vital to freeing you from the drama created by your enslavement to your emotional reactivity, which is caused largely by your inability to recognize the irrationality in your self-talk. That understanding also helps you to recognize how you are being constantly manipulated by yourself, others, and culture in general, in order to move you toward them and away from your life compass. The quicker you recognize and challenge the effectiveness of this nonsense, the quicker you wake up, which means that the world has one more powerful voice to help it awaken. Just reading through these explanations of common formal cognitive distortions, taken from a chapter in “Waking Up,” will make it more likely you will spot them, not fall for them, and will be less likely to commit them yourself. It is not enough to learn how to think, which is what you are doing when you discover and neutralize your emotional cognitive distortions. You need to learn how to think about thinking, or to understand the rules of thinking, so that your thoughts and arguments are rational. Formal cognitive distortions are the rules that govern thinking.Your thoughts are explanatory premises that generate feeling conclusions. Every emotional cognitive distortion is a failure in logic. This means that the feeling conclusions you reach about your life do not follow rationally from the assumptions you have made about your experience. A formal cognitive distortion is one that does more: it breaks a law of reasoning. Formal cognitive distortions are not untrue because they cause you to make bad life decisions; because they are untrue, you make bad life decisions. While both emotional and formal cognitive distortions are errors, formal fallacies are mistakes either in your assumptions or in the conclusions that you draw from them. They do not so much make you depressed or anxious as keep you stuck in thinking you’re right when you’re wrong, sane when you’re delusional, clear when you’re muddy, and straight when you are as twisted as a barrel full of eels. Formal cognitive distortions are evidence that you are either not thinking clearly or are thinking clearly in an abusive, manipulative, selfish way, as in the persecutor role of the Drama Triangle. While emotional cognitive distortions are self-destructive ways of justifying your feelings, formal fallacies are generally due to either ignorance or a willful desire to misrepresent the facts in order to get the upper hand in some situation. They are called “formal,” because while they are irrational, like emotional cognitive distortions, they involve ignorance of or the willful breaking of laws of “formal” logic. Many of the emotional cognitive distortions fall into this category as well, but the difference is that you can stop making an emotional cognitive distortion in one situation and continue with the same error in other parts of your life if you do not understand or follow the underlying rule, guideline, or “law.” Think of emotional cognitive distortions as more situation-specific while formal cognitive distortions apply to every and all life situations. For example, you may understand how you amplify the accomplishments of others and minimize your own, and then substitute a healthy alternative, such as, “I can choose not to compare myself to others.” However, until you understand and apply the underlying formal cognitive distortion of making hasty generalizations, this problem may show up in other areas of your life, or you may be less likely to recognize it when other people use it. There are many benefits to learning to recognize formal cognitive distortions. You will be better able to eliminate whole categories of potential problems, whereas recognizing emotional cognitive distortions tends to only eliminate them in discrete situations. For instance, it is one thing to eliminate black and white thinking in relation to you emotions; it is another entirely to eliminate it in thinking itself, as is done when you understand the fallacy behind Aristotle’s Law of Excluded Middle, as we shall see below. You will think more clearly and therefore make better decisions. You will also be much more likely to recognize the massive and thick cloud of formal cognitive distortions that are directed at you by media, your professional community, politicians, helpful friends and family, and by the spiritual paths that you trust. You will begin to notice them and find them everywhere. As a result, you will be better able to ask questions of what you read, hear, and what others tell you, and your questions will be much more likely to get to the heart of the matter and supply you the information you need: “Is this source trustworthy? Does it make sense? Does it know what it is talking about?” Your improved ability to ask questions will also communicate to others that you have expectations about clarity, reasonableness, and rationality that are important to you. By expressing those expectations you will create a culture for yourself of people who share a respect for such questions and interests while those who do not will select themselves out of your life. This may be a problem if you suffer under the delusion that you either can or should be all things to all people, or that unconditional compassion means acceptance of nonsense or letting others inflict foggy thinking on you in the name of love. Is that a loving act toward either yourself or someone you respect and care about? Clarity is one of the six core processes that are associated with the six stages of each breath: waking, aliveness, balance, detachment, freedom, and clarity. Cognitive clarity, which is the major gift bestowed by understanding formal cognitive distortions, is not the most important attribute, but only one of six to be integrated in a dynamic, interdependent balance. Think of learning the laws of reason and evolving out of fuzzy irrationality as laying the foundation you need to attain the higher order integration of the six core qualities of confidence, compassion, wisdom, acceptance, inner peace, and witnessing. Developing clarity of thinking will also help you avoid depression and anxiety by helping you break your addiction to emotional cognitive distortions, which damage you by causing you to act on wrong or irrational conclusions, think incorrect, untrue, or unhelpful thoughts, and feel self-destructive feelings. For example, if you think, “I failed; therefore I am a failure,” you are unlikely to try again, which is an example of not acting as a result of a wrong and irrational conclusion. It is thinking an incorrect, untrue, and unhelpful thought, because just because you fail at something it does not logically follow that you are a failure. Such thinking causes you to feel self-destructive feelings of worthlessness. If you allow your thinking to be determined by your beliefs and emotions, your biases and assumptions will keep you from thinking clearly. As a result, your life happiness and success will be determined by the nature of your delusions. Successful Argumentation “Argumentation,” or the art of challenging and supporting points of view, is not simply something we encounter in our relationships with others. It also involves our responses to what we see, hear, and read as well as how we think. For example, your thoughts are a form of argument with yourself, but your assumptions generally go unrecognized and unchallenged. The result is a life spent naively assuming the truth and validity of ideas and experiences which have never been thought through, and so are likely to be neither true nor valid. Consequently, you are vulnerable to the simplest of questionings by others, if you have never learned to examine the assumptions on which your beliefs are based. There is a simple tool for examining the effectiveness of your arguments, whether with others or in your own thinking, known as “Graham’s Hierarchy of Disagreement.” It puts types of arguments into a seven-point hierarchy, moving from ineffective and irrational at the bottom to decisive and rational at the pinnacle: To this we could easily add more levels at both the bottom and the top. For instance, ignoring or repressing the existence of a different point of view constitutes complete dismissal, followed by rejection of the argument as worth debating at all. This is followed by a recognition that a counter-argument exists, but is irrational, and therefore not worthy of consideration. This is in turn followed by a discounting of the argument, as “juvenile,” “immature,” or “sophomoric.” One additional attempt at deviation occurs before arriving at the bottom level of Graham’s pyramid, and that is attempted re-direction. If I can get you to focus on something else, like what you have done or not done, or some different issue entirely, I do not have to defend my argument. So we can see that there are at least five different levels of the pyramid before overt confrontation occurs. You will observe examples of each of these prior levels, as well as Graham’s levels, in the formal logical fallacies we address in this unit. In addition, there are forms of disagreement that are higher than explicitly refuting the central point, which is the top of Graham’s pyramid. Simply showing someone that they are wrong through a statement of refuting evidence is sometimes a necessary display of power, intelligence, and truth. However, direct refutation is most likely to arouse defensiveness and counter-attack rather than listening or agreement. Therefore, a more artful intervention involves Socratic questioning, which is designed to bring the other party to an awareness of the limitations and inconsistencies in their own argument. A still more adequate response is to present an example, generally in the form of a story, metaphor, or allegory, that demonstrates the absurdity of argument and counter-argument by objectifying and therefore relativizing and de-personalizing both. For example, instead of meeting the arguments of psychological geocentrism with some form of psychological heliocentrism, one could relativize them both by explaining how they are both transcended and included by a polycentric worldview. Psychological geocentrism is the idea that the world is all about me, which means that I take everything personally. Psychological heliocentrism is the idea that the world is all about some projected, ideal “me,” generally called the “Self,” “soul,” or “God.” A polycentric worldview recognizes the relevance and validity of all perspectives, because they can access all others, while still recognizing that some worldviews transcend and include others and are therefore more accurate, adequate, and valid. Another example is the famous Uncle Remus story of Brer Rabbit and the Tar Baby (which we visited in a previous unit), in which Brer Fox catches Brer Rabbit by fashioning a tar baby, complete with clothes and hat, and puts it in the middle of a country lane where Brer Rabbit hops by every morning. When Tar Baby does not respond to Brer Rabbit’s sunny “Good Morning, Tar Baby!” Brer Rabbit takes it personally and threatens to sock him to teach him some manners. Since Tar Baby still does not respond, Brer Rabbit first hits him with a left hook, getting his paw stuck in the tar. Outraged, he tells Tar Baby that if he doesn’t let go and tell him “Good Morning,” he will have to sock him again with a rabbit punch. This continues with one leg, then the other, then with a head-butt. The result is that Brer Rabbit is stuck in tar in the middle of the country lane, a dirty meal for Brer Fox. The point is that attacking, or arguing with, irrationality or pre-rationality, simply gets one stuck in tar. A higher order response is to recognize this reality and refrain from engagement, if possible, and to do so without an air of intellectual superiority, which implies phony confidence and deep fears of inferiority. Such avoidance is not always possible. An important, sometimes essential way to earn attention and respect is to show that you know what you are talking about, and you do that by laying out the facts, but in a way that is not directed at refuting your opponent. An excellent way to do so, famously used by Benjamin Franklin in his debates in the Continental Congress, is to begin by agreeing with and praising the legitimate aspects of your opponent’s argument. This causes them to not feel personally attacked, so that they are much more likely to listen to your counter-arguments. The point is to recognize that your clarity is determined by the level and style with which you deal with both the arguments of others and those that you have with yourself. Recognizing logical fallacies when they arise is one way to save yourself and others hours, days, or years spent in pre-rational belief systems or stuck in arguments about things that are not worth your time or energy. As we go through a list of common formal cognitive distortions in this unit, we will describe how and why each is a logical fallacy and how each reinforces both drama and various emotional cognitive distortions. There are many more than are described here; we are highlighting some of the more common ones with the goal of emphasizing their importance and their pervasiveness in thinking, conversation, and culture. As we go through a list of some of the more common and therefore important formal cognitive distortions, we will indicate how and why they relate to emotional cognitive distortions as well as to generating drama in your life. The following list of fallacies addressed here is hardly complete; there are many more! Why are there so many formal cognitive distortions? It’s because humans are so good at repressing, denying, confusing, and avoiding that we normally don’t even realize that we are doing so. And that is why we need to learn how to think about thinking, so we do not embarrass ourselves while impeding our growth into clarity. See how many of these you can spot in your world: False Dilemma (Excluded Middle) Straw Man Dogmatism Hasty Generalization Ad Hominem Argument From Authority Argument From Ignorance Tu Quoque Band Wagon Circular Argument Emotional Appeals Fallacy of Exclusion |

| Excluded Middle/False Dilemma:

This formal cognitive distortion presents an issue as a conflict between two extremes with no possible room for middle ground or nuance or compromise. You will recognize it from our discussion of the emotional cognitive distortion, black and white or “all or nothing” thinking. It is also known as the “Either/Or or False Dilemma” fallacy. What gives it a place here, as a formal fallacy, is that it is not only an emotional defense but a mistake in reasoning, completely apart from emotion. As you read the following list, see if you can spot why these statements are mistakes in reasoning:“I’m either a success or a failure.”“People either like me or I’m a loser.”“You are either for me or you are against me.” “She loves me; she loves me not.” “You work with dreams? You must be a wooly-brained New Ager.” “You are either a believer or damned to Hell.” “You’re a German Christian? So was Hitler. You must hate Jews.” “You’re a capitalist? You exploit people and plunder the planet for profit.” “You don’t support the Israeli occupation of Palestine? You must be an anti-Semite.” “You either support the US or you support the terrorists.” The problems that arise from this type of polarized non-thinking are fundamental and important. When you think this way you create conflicts where none exist. This is the stuff broken relationships and world wars are made of. It’s that serious. Fortunately, the solution is simple, if a person will simply use it. To avoid this fallacy, simply ask, “But aren’t there other possibilities?” All you have to do is reframe each of the above statements in a rational way and “presto!” the problem either disappears or becomes much smaller. Is that too good to be true? Let’s look at some substitutions and experience what happens to the “conflict:” “I’m either a success or a failure.” “Sometimes I succeed, sometimes I fail; I do not have to label myself as a success or failure.” “People either like me or I’m a loser.” “Some people will like me; others won’t. I don’t have to base who I am on others’ opinions of me.” “You are either for me or you are against me.” “We may agree on some things and disagree on others. I do not have to take our disagreements personally.” “She loves me; she loves me not.” “She may not know if she loves me, or she may feel different things besides love toward me.” “You work with dreams? You must be a wooly-brained New Ager.” “Anyone can work with dreams because dreams are universal.” “You are either a believer or damned to Hell.” “Believers can be criminals and non-believers can be saints.” “You’re a capitalist? You exploit people and plunder the planet for profit.” “Capitalists do not have to put profit before people and protection of natural resources.” “You don’t support the Israeli occupation of Palestine? You must be an anti-Semite.” “Palestinians are Semites and they don’t support the occupation.” “You either support the US or you support the terrorists.” “By many definitions of terrorism the US is a terrorist state.” Did you notice a shift in both understanding and feeling when you substituted the rational statement for each irrational one? This is a movement toward objectivity and relative neutrality, or a place of neither agreement or non-agreement. Or, perhaps the substituted statement raised a direct contradiction to the irrational belief. The result is that you are catapulted out of cultural groupthink and into a space of relative freedom and clarity, from which you can make better decisions. If the excluded middle is so easy to spot and so simple to correct, why does it survive? The simple reason is that it justifies what people want to do. For example, if you want to hate, attack, or kill someone the first thing you need to do is demonize them. If you get challenged at this, or do not allow yourself to do so, it is much harder to justify attacks of all kinds. The historical US stance of “exceptionalism” is a nationalistic expression of this logical fallacy: “There is me, and there are all the rest.” The belief that things either are or are not was codified in Aristotle’s rules of logic before three hundred BC. This principle is commonly known as “the Law of the Excluded Middle.” It says that you can either have A or not have A; you can’t logically have both A and not A. You either have a chicken or you don’t; you either have a name or you don’t; you either are alive or you are dead. A thing either exists or it does not. Something is either true and real or it is false and an illusion. What Aristotle did with this principle was codify black and white thinking and the Excluded Middle fallacy into Western logic. That irrational conclusion has been thought logical and rational, with devastating consequences, up until the present time. It is only recently, largely because of the rediscovery of the brilliant realizations made centuries before by the Buddhist sage and mystic, Nagarjuna, that thinkers are beginning to wake up out of their irrational slumber. In the 1st century in northeastern India, independent of Aristotle, without knowledge of his logic, and for totally different reasons, Nagarjuna thought through the Law of the Excluded Middle and recognized that this was a fallacy. He realized that outside the disciminations and dualisms fundamental to the working of thought that life itself is not in one category or another. Categories and distinctions are created by the mind, not life, and when you step outside of the mind and language you can see that this is a law the mind uses to think, but that it is itself irrational. Nagarjuna probably came to this conclusion due to two major influences. The entire teaching of Gautama Buddha emphasizes the importance of finding balance between extremes, or “the middle way.” This principle was so fundamental and important to Gautama that this is what his teaching was called, not “Buddhism,” which was a name given to it by non-Buddhists. Nagarjuna wanted to discover how the middle way functioned in the operations of the mind. The other major influence was his direct and personal experience of non-dual states, first in meditation and then generalized into clear, non thought-mediated perception in his everyday life. When Nagarjuna united these two influences, one philosophical and the other personal and experiential, the result was the creation not only of a new, deeper way to understand the fallacy of the Excluded Middle, but a powerful meditation tool. In his famous “tetralemma,” Nagarjuna observed that there are four possible ways of considering anyone, anything, any idea, emotion, or experience. Either: “It is.” (“It exists.”) “It is not.” (“It does not exist.”) “It is both this and that.” “It is neither this nor that.” Nagarjuna discovered that when you suspend all four of these assumptions you inevitably find yourself not only outside of Aristotelian logic; you effectively move your cognitive processes into neutral. It becomes impossible to interpret, analyze, or reason. Don’t believe me; it is far too important to take anyone’s word on this. Try it now. Take a thought of your choice and suspend all four of these possibilities. Let’s say you look at your hand. It exists as an experience mediated by a mental concept, the word “hand.” Now suspend that concept by telling yourself, “My hand does not exist.” By this you may mean it is energy, or a figment of your imagination, or whatever, but the point is that your hand no longer exists for you. Don’t just imagine that intellectually; try to believe that it is true, that your hand really does not exist. Now suspend the assumption that therefore it does not exist. What happens? You are no longer affirming the reality of your hand, nor are you denying its reality. So where is it? What is it? Now take the next statement, “It is both this and that,” and deny it. If neither of these statements are true, that it both exists and does not exist at the same time, what does that mean? Where and what is your hand? Finally, take the last escape hatch for your rational mind. Take the only remaining possibility and deny it: “My hand neither exists nor does it not exist.” Now feel what the result is. Do you experience how your mind now is deprived of any and all ways to grasp, understand, or deal with the experience of what you call your hand? You have launched yourself into a meditative, open, but fully conscious and present space in the here and now, because you have shifted the discriminating powers of your thought into neutral. Notice that your experience of your hand continues to exist. Nothing has changed experientially; what has changed is that your thought processes can no longer “stand in,” “represent,” or “signify” your “hand” with a word as a form of mental shorthand or shortcut. Instead, nothing “stands for” or “mediates between” the experience of your hand and “you.” There is no distinction between “you” and your “hand.” Now imagine if you extended this thought experiment routinely to everyone and everything in your life. What would be different? You would still use the shortcuts of your mental distinctions whenever you wanted, but they would no longer be the default or assumed structure that you use to experience the world. Notice that the way you experience the world when you do this experiment is not the same as pre-rational experience. Following Nagarjuna’s tetralemma does not regress you to a pre-personal, pre-rational fusion with oneness. Your ability to think rationally and make distinctions still exists; you have simply parked it in neutral for the time being. However, with pre-rational levels of development you can’t give up rational thought processes because you aren’t yet rational. Your experience is mediated by your emotional preferences and your beliefs, but not rationality, because you have not yet learned to think, much less think about thinking. You can’t give up your rational identity if you haven’t yet formed one. You can’t outgrow formal cognitive distortions if you don’t even recognize when and how you use them. This is why the transpersonal really does lie on the other side of the rational and that there really is a difference between pre-personal and transpersonal experience. This is why those who claim transpersonal developmental levels but who are still wedded to pre-rational beliefs or who do not demonstrate a familiarity with formal cognitive distortions have probably mistaken access to transpersonal states via psychic, mystical, or near death experiences for stable, ongoing access to transpersonal stages of development. They aren’t nearly as evolved as they think they are. No one automatically learns to be rational or how to think about thinking. These are skills that are not hard-wired, like walking or talking, or survival skills taught in most families or cultures. On the contrary, they involve questioning authority, which can be life-threatening at pre-personal levels of personal and social organization. Therefore, families and societies tend to discourage learning these skills, except in specific, well-defined ways, like philosophy, math, and technologies. This is why much of the information on cognitive distortions in the previous chapter, the current one, and the subsequent one, may be new to you: society has not recognized adaptive or survival value in learning these things. Learning to discriminate between rational and irrational thinking can come into direct conflict with family, business, religious, and governmental interests. Nevertheless, if you desire to grow into personal levels of development, learning how to think and to think about thinking are requirements; they are not optional. They are pre-requisites to your evolution into higher stages of development. All the hard work you are doing to recognize emotional, formal, and perceptual cognitive distortions makes possible growth into radically freeing, open, and accepting transpersonal perspectives that you could not access before, because even in mystical state openings, lucid dreams, or near death experiences lower levels of development necessarily distort and misinterpret them. IDL teaches you how you keep yourself stuck in drama and then gives you tools to witness both your thoughts and feelings while accessing non-dual perspectives. The practical advantage of cultivating the ability to be present in such a space is that it is free of drama. You are in the world but not of it. Bad things still happen, but they do not happen to the “you” that is free, that is at complete peace, and which witnesses all of the dimensions of human experience without judgment. Do you see the importance of the fallacy of the Excluded Middle? When and where do you see it in your world, relationships, and thinking? When are you vulnerable to it? How do you respond to it? What do you want to do about it? How might your life be different if you recognized and eliminated this formal cognitive distortion? Middle Ground Wile E. Coyote Disappearing into the Middle Ground Learning to experience a “middle ground” between the dualities of life is different from declaring an irrational compromise. A middle point between two extremes is not the same as the truth. Sometimes a thing is simply untrue and a compromise is also untrue. Half-way between truth and a lie, is still a lie. This is also known as the “Golden Mean Fallacy,” or the “Fallacy of Moderation.” Because “enough” is the middle ground between “too much” and “too little,” it does not follow that “enough” either the logical or rational choice. For example, if you want to build strength and endurance you need to push your body past its comfort zone and out of its “middle ground.” Holly said that vaccinations caused autism in children, but her scientifically well-read friend Caleb said that this claim had been debunked and proven false. Their friend Alice offered a compromise that vaccinations cause some autism. Straw Man |

| The Excluded Middle fallacy is closely related to the Straw Man fallacy, which essentially paints one side, instead of both, as so extreme no can agree with it. It is used to misrepresent someone’s argument to make it easier to attack.They are betting you are either too ignorant or stupid to recognize that their argument is a re-direction from either what you actually said or a misinterpretation of your position. Often this is done by referring to the exception, rather than the rule, and inferring that the exception is the rule.Here are some examples:“Scientists say we all come from monkeys, and that’s why I homeschool.” (But science doesn’t say we come from monkeys.)“You’re a German Christian? So was Hitler. You must hate Jews.” (But you aren’t Hitler.)

“All Greenpeace supporters support the sinking of whaling vessels.” (Just find one Greenpeace supporter who disagrees to knock down this Straw Man argument.) “If you surrender your freedoms, the terrorists have already won. You don’t want that, do you?” (Just find one example of deprivation of freedoms by non-terrorists to knock down this Straw Man argument.) “Stalin supported gun control, you know.” (Reasons for gun control exist independent of Stalin’s decisions. Therefore, the introduction of Stalin into the argument is a Straw Man fallacy.) The Straw Man fallacy is common in advertising and political smear campaigns. One creates the illusion of refuting an opponent’s argument by mischaracterizing it and then knocking down that mischaracterization. This can sound impressive if you are not familiar with the position of the opponent, as most listeners are not. Therefore, this logical cognitive distortion works because it assumes you are either ignorant or stupid and then takes advantage of your lack of information to persuade you of its truth. Consequently, the Straw Man fallacy is an example of willful manipulation. However, it could be that the speaker is honestly misrepresenting their opponent’s position based on their own lack of familiarity of it. For example, if you said in the past that you hate immigration because it takes jobs away from citizens, but have since changed your position to believe that immigration is good, an opponent can accurately cite your previous position and triumphantly pronounce you wrong. Because a living source may have changed his opinion, be particularly careful about attacking something he no longer believes. This is a good example of why you need to get in the habit of doing two important things. The first is to suspend your judgment. This is very similar to the phenomenological stance of IDL during the interviewing process. The second is to gather information by asking questions. Are the speaker’s statements accurate or not? It is easier today than ever to fact-check statements and therefore hold speakers and writers accountable. For example, entire sites like “Snopes” allow you to check to see if a story is an urban legend or not. Fact-checking is a form of asking questions of the speaker or writer. Are they credible? Are their claims based on the actual position of their opponent or are they raising a Straw Man argument that they can triumphantly kick to the ground? Do you think the Straw Man fallacy is important? When and where do you see it in your world, relationships, and thinking? When are you vulnerable to the Straw Man Fallacy? How do you respond to it? What do you want to do about it? How might your life be different if you recognized and eliminated this formal cognitive distortion? Once you recognize this fallacy, what can you do about it? People who use Straw Man arguments need to be confronted, because if they aren’t, they will keep using them as a form of predation on the ignorant. It is only when such people recognize that they will not be able to get away with this, or any, formal cognitive distortion that they will stop using them. Dogmatism |

| Dogmatism is a formal cognitive distortion in which your position is so correct that others should not even examine the evidence to the contrary. It is marked by always needing to be right, which is itself an indicator of the persecutor role in the Drama Triangle and first tier development. When you use dogmatism you are unwilling to consider alternatives to what you are sure is right or true. We do not normally think of chronically depressed people as being dogmatic, but if you apply the above definition, it is obvious that they are. When you are depressed, you are sad because you just are. You are a failure because you know you are. Jesus is Lord because you feel it in your heart. You are right because you know the truth. Out of all the many possible or alternative possible ways of seeing, feeling or behaving, only yours is correct, and that is because you know it is. If pressed on this, you may appeal to some untestable reality, “intuition,” or to some unavailable authority, such as “God’s will,” “divine order,” or “karma.” These are not explanations; they are justifications. There is a difference.The strategy employed by those who use this fallacy is to stifle dissent before you can even think of questions to ask. Even when many, perhaps millions, of other people believe otherwise, only you can be correct. You have seen God and He has told you the Truth. You are the parent, so you “know” what is best for “children” everywhere. Those who disagree with you are “biased”, while you are “objective.” If it is your friend, employee, child, or spouse that is disagreeing with you, he or she is the one who is “disobedient” and “disrespectful.” Dogmatism is closely related to the Excluded Middle fallacy, because it assumes that competing ideas or viewpoints cannot co-exist within single systems. It is authoritarian and absolutist in that there is an unwillingness to even consider another point of view.Dogmatism is also a more general type of fallacy found in all formal cognitive distortions. At best, an explanation appeals to testable, verifiable evidence; a justification is a dogmatic assertion that cannot be verified. Therefore, when someone makes a pronouncement without evidence or providing a means by which others can evaluate claims that are made, they are practicing some form of dogmatism.A good example of dogmatism is a belief in unverified miracle cures like positive thinking, prayer, reiki, and energy medicine. Believers continue to believe, in the absence of evidence, justifying their belief by saying, “They haven’t done enough of the right kinds of studies;” “They are suppressing the evidence because it is a threat to their professional cartel;” “Science hasn’t advanced far enough. Some day they will discover that I am right;” “It’s part of a conspiracy to turn us all into brainless zombies.” Are these reasons or are they dogmatic excuses, rationalizations, and justifications for not dealing with inconvenient truths?

What would you think of someone who claimed that socialism is morally wrong, even though they attend a public university, meaning that taxes support their education? Aren’t they taking a dogmatic position that their behavior contradicts? What would you think of someone who stated that welfare is wrong and all those who partake in it are lazy, even though they accept federal financial aid, as all members of society do, in one form or another? Isn’t this another example of a dogmatic assertion that is proven false by one’s own behavior? We can see that dogmatism relies not only on black and white thinking but on hypocrisy, in that the speaker is blind to their own violations of the principles they are proclaiming. It is also dogmatic to proclaim that certain types of dream figures like angels are “good” and others, like monsters, are “bad,” because there is no evidence presented or way that the statement can be verified. It is true because the long, venerable tradition of dream interpretation says so. People who use the dogmatic fallacy are generally so rigid in their beliefs that their existence largely serves as an example of who not to be, yet their confidence inspires trust in those who have not yet learned to think for themselves. The development of dogmatic people is fixated at pre-personal levels; they are locked into the delusion that they are rescuers in the Drama Triangle. They will most likely learn the hard way, because they are in no position to listen to reason. Therefore, your responsibility is to protect yourself and others from them. One way you can do this is by using their dogmatism as an opportunity to educate others on the importance of recognizing this and other cognitive distortions. Do you think this formal cognitive distortion is important? When and where do you find it in your world, relationships, and thinking? When are you vulnerable to dogmatism? How do you respond to it? What do you want to do about it? How might your life be different if you recognized and eliminated this formal cognitive distortion? Hasty Generalization |

| This formal cognitive distortion, also known as “Misunderstanding Statistics” or “Non-Representative Sample,” is related to the emotional cognitive distortion of exaggeration or overgeneralization, and is therefore found in many different logical fallacies, such as the “Argument from Authority.” It mistakes a small incidence for a larger trend. People do this all the time with anecdotal evidence. Anecdotal reports of miracle cures are often used as testimonials to lure the gullible into parting with their money seeking placebo treatments. If they understood the formal cognitive distortion of hasty generalization they would say, “Wait a minute! This is an impressive result, but impressive results normally happen with placebos. Is there any research that shows that this treatment performs above chance?” Because a friend’s cancer went into spontaneous remission when they started drinking wheat grass you decide wheat grass kills cancer. This is an example of lazy and sloppy thinking: we can’t be bothered to check our assumptions, because they are comfortable and agree with what we want to believe.A related fallacy has been called “Composition/Division.” It assumes that what’s true about one part of something has to be applied to all, or other, parts of it. This is because often, when something is true for the part, it does also apply to the whole, but because this isn’t always the case it can’t be presumed to be true. Because you respect someone as an authority in area “A,” you assume they are also an authority in areas “C,” “L,” and “Z.” It says, “because Einstein knows a lot about physics, he must also know a lot about God, religion, philosophy, psychology, relationships and ballet.” “Because Fred has amazing lucid dream experiences, he must be enlightened.”When you rely too much on authority, whether as power or knowledge, you are indulging on the fallacy of hasty generalization. You are giving your power away to those who may not have earned your trust. View the authorities you rely on as resources for decision-making, rather than as providing the final say concerning any issue. For example, the theory that IDL uses, such as this information on cognitive distortions, is meant as a guide to your own verification procedures rather than to be taken as a source to be trusted. Perspectives are not authorities; they are just perspectives, but some perspectives are more legitimate than others. Trust your inner compass! Question all sources of authority!Hasty Generalizations are often attempts at self-rescue in the Drama Triangle because they draw false, exaggerated conclusions designed to defend you in some way. That you feel you need to use them indicates that you are feeling victimized by something or someone. Its use confirms your suspicions, deepening your addiction to Drama. The fallacy of Fairness is another example of hasty generalization. Your partner cheats on you and you conclude that’s not fair, which leads to you not trusting him or her at all, even though he or she is a good listener, parent, provider, and organizer. If you no longer draw the conclusion of fairness, or the lack of it, then other emotional reactions open up. You could laugh at the situation. You could be thankful your partner is getting his or her needs met. You could remain an adult and ask what’s going on instead of jumping to conclusions.

Gambling and winning the first time out is an example of an often disastrous hasty generalization: “If I won once, I will win again.” A rational assessment concludes that casinos stay in business because bets are rigged so that the more you play the more likely you are to lose. Fishing also frequently tricks us into this fallacy; you get a hit on your first cast and assume you’ve found the perfect spot and the ideal lure, only to sit there with nothing for the next hour. If you grow up in a very white neighborhood and only see blacks on TV, you are likely to think that most black men are athletes, gangster rappers or comedians. Do you think this formal cognitive distortion is important? When and where do you see it in your world, relationships, and thinking? How do you respond to it? When are you vulnerable to making hasty generalizations? What do you want to do about it? How might your life be different if you recognized and eliminated this formal cognitive distortion? Ad Hominem |

| Ad Hominem translates as “to the man” and refers to attacks on some opponent, rather than on the validity of their evidence or logic. It says, “I can’t win on evidence or logic, so I will attempt to convince people that you are untrustworthy.” Another name for this logical fallacy is “character assassination.” “If I can’t beat you with the facts, let me see if I can destroy your reputation.” Ad Hominem, also called the “genetic fallacy,” because it bases arguments on their source rather than on reason, is the formal fallacy behind the emotional cognitive distortions of labeling and mislabeling. It is one of many examples of changing the subject, which is the underlying function of many formal cognitive distortions. If I can distract you from what is logical, rational, and the facts, you may join me in my groupthink. Ad hominem attacks use labeling to justify ignoring facts or abusing someone. It is one thing to say, “I don’t agree with you,” but it’s another to say, “I don’t like you.” When you judge something as good or bad on the basis of where it comes from, or from whom it comes you are commiting a type of “red herring” fallacy. Genetic fallacies are like ad hominem attacks, but they deal with sources rather than character.If someone is labeled a terrorist, if a politician is finding a need to denounce someone, or if a friend or colleague at work is gossiping about someone, ask yourself, “Could this be an ad hominem attack?” Better yet, if someone is criticizing another person at work or on the news, start with the assumption that it is an ad hominem attack. An excellent current example in the world today is the villification of Vladimir Putin, President of Russia, in the Western press. Could this be an ad hominem attack? The next question to ask is, “Do Western governments and media have a reason to discredit Putin? Is this person a threat to them in some way? What, if anything, does President Obama or Hillary Clinton have to gain by turning my attention to the negative qualities of someone else?” Rule that assumption out first. It is not until we understand this game and why people play it that we can confront it and thereby force them to stop playing it. People use personal attacks because most of us don’t recognize when and how we are being manipulated by attempts to trash someone’s reputation. As always, the solution is first caveat emptor – beware! Question! Doubt! Be skeptical! What are you being sold, and why? This principle applies not only to politicians but to all sales and marketing as well as to friends and “spiritual organizations.” You can ask questions, both in your own thoughts and to others without thereby being cynical. Ask questions and gain information.Global labeling is another example of the ad hominem logical fallacy. Because we can’t or won’t think things through, we stop thinking and start attacking the person rather than the argument, as Hillary Clinton did when she compared Putin to Hitler. Doing so is a sign of defeat, small mindedness, a lack of respect for the intelligence of one’s audience, and an embarrassing reflection on our own lack of ethics.Villifying a person is much easier than defeating their arguments. You’ve already lost the argument when you attack the character of your opponent; you just don’t realize that you have. Anyone who understands formal cognitive disorders will recognize that those making ad hominem attacks are merely demonstrating their ignorance and intellectual immaturity.

Interestingly, blaming yourself, as a form of self-persecution, is an example of a self-directed ad hominem attack. Instead of debating the effectiveness of what you are doing or analyzing what went wrong so you don’t do it again, you attack your own character! Perhaps it is because such irrational self-persecution is so common that people get away so frequently and easily with making ad hominem attacks. Are we so used to attacking ourselves that we think nothing of it when we experience someone attacking a third party? Personalization is an imaginary and self-inflicted type of ad hominem logical fallacy in which you assume other people are attacking you. If they attack your evidence or logic, you take it as an ad hominem attack on yourself. This is a reminder that ad hominem, as with all logical cognitive distortions that are used as weapons, are first statements about the ethics and level of development of their source. Their behavior, methods, and strategies reveal their character. Another interesting example of ad hominem arises in our dreams when we react to the appearance or the “character” of a dream monster instead of listening to, considering, and addressing whatever issues he presents. Do not take ad hominem to imply that all criticism of others or yourself is either unjustified or not useful. However, criticism is best directed into questioning, combined with the presentation of constructive solutions, rather than at your character or that of someone else. Nevertheless, there are levels of moral and self development, and our actions create the basis on which people make judgments about how trustworthy, reliable, and supportive we are likely to be. Do you think this formal cognitive distortion is important? When and where do you see it in your world, relationships, and thinking? Have you ever been the victim of an ad hominem attack? How did you feel? How do you respond to it? When are you vulnerable to using ad hominem attacks yourself ? What do you want to do about it? How might your life be different if you recognized and eliminated this formal cognitive distortion? Argument From Authority |

Unthinking respect for authority is the greatest enemy of truth. – Albert Einstein

| Because an authority thinks something, does it follow that it must therefore be true? Because an authority recommends something, does it follow that it must therefore be good for you? This formal cognitive distortion is the flip side of the ad hominem; in this case, the argument is advanced by appealing to the character of someone: “Support the US, because President Obama is a black and he won the Nobel Peace Prize.” “Buy Wheaties, ‘The Breakfast of Champions,’ because these sports stars endorse it.” The hope is that by connecting my argument or product to someone you respect that you will trust them and not give me, my products, or my arguments too much scrutiny.This fallacy should not be used to dismiss the claims of experts, or scientific consensus. While appeals to authority are not valid arguments, it does not follow that it is wise or rational to disregard the claims of experts who have a demonstrated depth of knowledge, unless one has a similar level of understanding.Sometimes arguments from authority are obvious because the endorsement comes from a clearly false authority, such as a supermodel who pushes cosmetics or a pro athlete who advertises home loans. However, because we are lazy and ignorant, we want to trust and believe, particularly when the preferences of some authority agree with our own.Since childhood we have based our sense of self on modeling the behavior of all sorts of “authorities.” In fact, the scripting that creates both your reality as well as your very identity is largely an expression of this cognitive distortion. You believe what you do not only about your family, nation, education, career choices, religion, and others, but also about who you are, because of the authority of those who were your formative influences when you were a child. Believing otherwise, that your beliefs are your own, is due to another fundamental formal cognitive distortion, emotional reasoning. This provides another good example of just how powerful and pervasive cognitive distortions are. They generate the delusions that we not only mistake for reality but use to generate our own identity.

The psychological hook that causes us to suspend our judgment and believe that someone is an authority stems from the Drama Triangle. Most of us are looking for someone to rescue us. If we will just trust this attractive, high-status person, our lives will be better. Why we continue to fall for this same old ruse is a testament to the undying gullibility of humanity, borne of our unwillingness to find, listen to, and follow our own inner compass. Dreaming provides an interesting example of the fallacy of argument from authority. You typically perceive dream events based on the authority of your waking perception, which is locked in its frame of reference and uninformed regarding the perspectives of the dream characters it encounters. Learning to listen to and trust the authority of interviewed emerging potentials is obviously not easy, nor should it be, because trust needs to be earned and claims need to be verified. Do you think Argument from Authority is an important formal cognitive distortion? When and where do you see it in your world, relationships, and thinking? When are you vulnerable to using arguments from authority yourself? What do you want to do about it? How might your life be different if you recognized and eliminated this formal cognitive distortion? Tu Quoque Meaning, “You too,” this is a fancy Latin name for a strategy for gaining the upper hand in an argument by changing the subject. For example, you say, “Based on the arguments I have presented, it is morally wrong to use animals for food or clothing.” Your friend says, “But you are wearing a leather jacket and you have a roast beef sandwich in your hand! How can you say that using animals for food and clothing is wrong!” Do you see what the problem is here? Just because you are a hypocrite and don’t practice what you preach does not disprove your argument! Your friend is answering your argument with blaming and counter-attacking. He or she is avoiding having to deal with the substance of your arguments by turning it back on you! Here is another example: I comment that you seem to have put on weight. You respond by pointing to my gut and saying, “Nice baby bump. When are you due?” Like all cognitive distortions, Tu Quoque lands you in the Drama Triangle, either as persecutor or victim. Defending yourself may only put you in the role of rescuer, which keeps you in the spin cycle of the cosmic samsaric washing machine. When you ask questions, in a non-threatening, non-attacking way, you increase the likelihood you can move the conversation both out of drama and to a higher, more rational, clearer level of discourse. Remember that rationality is not your goal but only a means to clarity, witnessing, and transparency: helping yourself and others to get out of your own way. Bandwagon |

| Bandwagon, is a “groupthink” fallacy that says, “If all these people believe it, it must be true; if all these people are doing it, it must be OK to do it.” We might also call it “adolescent herd instinct.” If you back off and look at the world objectively you will see that both history and the evolution of human consciousness is essentially the story of masses of people jumping on different Bandwagons. Millions of people believe in heaven, the virgin birth of Jesus, and his second coming, so these things must be true. The government says Putin and Russia are bad, so it must be true. Everybody is buying houses at these low interest rates, so this could not be an artificially inflated financial bubble that is going to devastate the economy when it bursts. Our country is being attacked by Them; it is our patriotic duty to go to war and kill them. Everybody loves this pop star, design, or fashion, so it must be good. Psychologists, doctors, and lawyers all supported the US torture program under GW Bush. Therefore, it must be OK. Our parents and culture believe in these things, so of course I do too.When you fall for the Bandwagon fallacy you get seduced to the popularity or the fact that many people do something as an attempted form of personal validation. This is most closely related to the early personal level of development, where identity is drawn from group memberships. I believe like my groups; they provide me with my identity. I don’t have to think, in fact it is better if I do not, because it may put me in conflict with my group if I do. If I go along, I will be rewarded by the group. If I don’t, it is very powerful and may blackball or scapegoat me. It has many, many ways it can ruin my reputation or my life if I do anything to distinguish myself from the values and practices of my group.It is much easier to see the flaws in this argument than it is to do anything about them. But awareness is the first, essential, and necessary step. Knowledge builds up to a critical mass when it turns into well-thought out, decisive action. In this case, that knowledge is awareness that the popularity of an idea has absolutely no bearing on its validity. If it did, then the Earth would have made itself flat for most of history to accommodate this popular belief.Bandwagon ignores the reality of non-majority information, facts, and arguments. It refuses to consider the probability that we are hopping on board yet another collective delusion. It is at the foundation of the madness of crowds, wars, and economic bubbles. When we enter into a groupthink we generally think we will transform it, but it generally ends up transforming us, because it is bigger and more stable in its beliefs and investment in its position than we are. For example, most young people go to work someplace thinking that they are going to make an improvement in the culture or productivity of the company. They do not believe that they are going to become a creature of the groupthink of that organization. However, most objective observers would agree that this is indeed what happens with the majority of workers in any business. This is because the pressures to conform, combined with the consequences for going against group culture, are so pervasive and immediate, that there are few ways to resist. We even see this in family cultures and how difficult it is for adolescents to find out who they are separate from their families of origin. The best most can do is experiment with various forms of rebellion, which have little to nothing to do with establishing their own identity, but instead involve conforming to various forms of peer groupthink.

When I still believed in souls and reincarnation I wondered how they could be so short-sighted and ignorant as to make obviously poor choices, in many cases, choices that resulted in pain and misery for themselves and others. One theory I came up with was that souls did the same thing we do: routinely underestimated the power of groupthink and the Bandwagon effect. From where they were looking, the path forward looked easy: “I’ll just get born, learn stuff, and awaken to myself.” The fact that this so rarely happens forced me to decide that either souls were very stupid or there weren’t independent minds making decisions about where to incarnate. The third option, that people chose to have bone cancer as children because it was their “karma,” was so disgusting, vile, and derogatory to me that I would no longer even consider it. Bandwagon has also been termed the basic fallacy of democracy, that popular ideas are necessarily right. When you look at the history of popular ideas in democracies, you find that they include race based slavery, legal cocaine, American women not being allowed to vote until 1920, prohibition, exceptionalism, democracy, capitalism, and of course the all-time favorite, war. An embarrassing patriotic frenzy accompanied the bombing of Baghdad at the beginning of the illegal attack on Iraq in 2003. CNN (Cable News Network), a primary global sources of news, displayed a picture of an American flag superimposed over night-time scenes of Baghdad being blown to bits. One of the most impressive current examples of bandwagon is the cult of positive thinking. While it is itself an example of a perceptual cognitive distortion, how and why it has become widely adopted is an example of the Bandwagon fallacy. We will discuss it in the next chapter on perceptual cognitive distortions. Bandwagon also describes non-rational thought processes that keep us locked in perceptual cognitive distortions, with the result that we stay asleep and miserable. Adolescents, in a natural aversion to groupthink born of a desire to find and create their own individuality, simply denounce one bandwagon for another. They trade Coke for Pepsi, all the time believing that Pepsi is “authentic,” or an expression of their own individuality, instead of recognizing what is obvious—they are adopting a “new, improved” bandwagon. The power of this delusion is so great that you and I are blind to the bandwagons that we are currently on. It is only in retrospect, in looking back at our lives that we can say, “Yes, during that period of my life I was really on that bandwagon!” Since we can say that about every period of our lives, isn’t it likely that we are now on other bandwagons and are just too subjectively immersed in them to see them? The proper conclusion to draw from the awareness that “everyone is doing it” is that “everyone must be equally hypnotized, unconscious, sleeping, dreaming, and sleepwalking.” The question then becomes, “What must I do to escape groupthink?” The answer IDL provides is the one you are currently exploring: learn the basic processes that keep you asleep, dreaming, and sleepwalking and then learn how to access, listen to, and follow the recommendations of your interviewed inner potentials in order to find and follow your inner compass. Do you think the Bandwagon fallacy is important? When and where do you see it in your world, relationships, and thinking? What bandwagons might you be currently riding? What do you want to do about it? How might your life be different if you recognized and eliminated this formal cognitive distortion? Personal Incredulity Because I don’t understand what you are talking about, it must not be true. I am saying that because I find something difficult to understand, it’s therefore not true. Is that right, or am I just too ignorant, lazy, or stupid to learn what I need to understand? For example, understanding the evidence for evolution by natural selection requires some familiarity with biology, anatomy, physiology, genetics, and geology. If I am ignorant of these topics it may easier for me to just say, “God did it,” and leave it at that. I once read a book explaining human evolution as interbreeding by extraterrestrials, because the human body was too amazing to have been created by natural selection. When you don’t know the answer, or are not sure what to believe, resist the temptation to reach for the simplest, most popular, or most comfortable explanation. These are generally not expressions of your own intellectual curiosity, but rather statements of your own willingness to succumb to groupthink. In our world it has never been easier to look at opposing theories on any subject and form a broader, more well-rounded opinion based on a summation of the state of knowledge on the subject as it stands in the world today. In fact, failure to do so today with the resources we have at hand is almost inexcusable. Circular Argument |

| Circular Argument, which is also known as “begging the question,” and “jumping to conclusions,” simply repeats the same argument over and over again, instead of providing substantiation for it. The conclusion is included in the premise. This logically incoherent argument often arises in situations where people have an assumption that is very ingrained, and therefore taken in their minds as a given. Circular reasoning is bad mostly because it’s not very good.You do this when you repeat a claim, belief, feeling, or the same flawed reasoning over and over again without ever providing support for your assumptions:“I know he loves me because he says he’ll never leave me, that I’m the only one for him, that he’d go crazy if I left him.”“Gay marriage is just plain wrong.”

“I can’t believe people eat dog. That’s just plain gross. Why? Because it’s a dog, of course. How could someone eat a dog?” “God exists because He tells me so in His Holy Word.” “Obviously logging causes severe environmental damage. You don’t have to be a scientist to see that; just go out and look at a clear cut and there it is: no trees.” “How could anybody date a geek like him – he’s a geek!” “I’m a loser. Why? Because I never win.” “ I deserve to be punished. Why? Because I’m a bad person.” “Global warming deniers are dangerous people because they deny global warming.” “You should be a loving person because the world needs more loving people.” “Dogs make better friends than most people because they are friendlier than most people.” If you read enough of these examples you start to see the underlying similarity of these arguments, and that is that they are tautologies. That means that they say, “A equals A.” No new information, no new reasons, are given for the belief in A. You believe in A because you believe in A. Belief in A is so self-evident that it doesn’t require proof. One more, rather ultimate example is, “I believe in God because God IS.” What is this statement saying? Essentially, “Don’t insult me by asking for proof or evidence in God because my belief is so obvious that it requires no substantiation.” Really? Is that true? Is there any belief that is so obvious that it requires no substantiation? This is the debate that separates pre-personal levels of development from personal levels. The former says, “Belief stands on its own; the Truth is the truth, and I know it is true because I have seen the truth.” The latter says, “Belief rests on assumptions. If these assumptions are not questioned, your life will be directed and controlled by beliefs that are merely assumptions. You will think you are free while you remain a slave to the belief systems in which you are imbedded.” As with other formal cognitive distortions, those who use circular arguments have no clue that they are being irrational and will even deny it when you directly point out to them the inconsistency of their thinking. This is why irrationality is dogmatic – it doesn’t recognize its irrationality while at the same time being utterly convinced it is being highly reasonable and rational. If you stop and think about it, how could irrationality, meaning an inability to think rationally, be expected to grasp a rational argument? It is rather like expecting a child to act like an adult or an animal to act like a human. There are different evolutionary and developmental steps, gradations, or hierarchies, and expecting rationality from a pre-rational consciousness is like expecting stimulating conversation from a mynah bird. This does not, however, excuse you from your obligation from knowing how to think yourself or to respect those who do not. If you do both, you will stay free from unrealistic expectations, unhelpful judgments, and the drama of others. It is not your job to educate those who do not ask you for help or support, but you can build bridges by asking questions, showing respect, being confident enough to be self-deprecatory, non-threatening, and humorous. Do you think it is important to be able to recognize circular arguments? When and where do you see them in your world, relationships, and thinking? How do you respond to them? When are you vulnerable to the fallacy of making circular arguments yourself? What do you want to do about it? How might your life be different if you recognized and eliminated this formal cognitive distortion? Burden of Proof |

| If you make a claim, such as “God exists,” it is your responsibility to prove it. It is a fallacy to say, “You can’t prove that God doesn’t exist.” In law, the burden of proof falls on the prosecution because defendants are presumed innocent until proven otherwise. An inability or disinclination to prove a claim does not make it valid. The more outrageous or out of the norm a claim is, the greater is the burden of proof that is required.If you are going to assume a belief or present something as a fact to others, you have an obligation to first decide whether it is a personal preference, like chocolate over vanilla, and leave it in the realm of complete subjectivity, unsubstantiated and and subject to proof or validation, or whether it is a position that you believe is more, a statement of fact or of belief that you think applies to others or should appy to others. For those beliefs in the second category, you need to first know what yours are. This is not as easy as it sounds, as most of our beliefs are unquestioned assumptions that we believe just because we do, not because they are rational or we have thought them through. The consequence is that if we are challenged on them, we are typically unprepared to adequately explain them or defend them. Therefore, you would be well-advised to take a look at your assumptions and ask yourself why you believe them. Are they based on fact or opinion? How do you know? What sources can you cite to back up your beliefs and opinions? If you cannot, then you really can’t claim you know what you are talking about. You are just a walking, amorphous cloud of assumptions, beliefs, and groupthink. Why should you expect others to take you and your beliefs seriously?This may sound harsh, but isn’t this the sort of credibility you expect from others? Do you want to accept someone else’s beliefs just because they feel good, or make sense to another person? If no, then why should others do so with your beliefs and ideas? |

Non Sequitur

|

| . |