This is Chapter Six from Waking Up, by Joseph Dillard

There are three types of cognitive distortions, all of which generate and maintain the Drama Triangle.

Emotional cognitive distortions are words or statements that you tell yourself or others that feel true, but when examined factually are found to be irrational. That is, they aren’t true; they only feel true. For example, when you say or think, “No one ever listens to me,” you are making a statement that may indeed feel true. However, all one has to do is think of one time you have said something and someone has responded to disprove this statement, revealing it to be an irrational statement and an emotional cognitive distortion.

Logical cognitive distortions are failed attempts at reasoning, whether to problem solve, persuade or manipulate. These include attacking the person making a point rather than the point itself, guilt by association, asking loaded questions, presenting false dilemmas and many more. Like emotional cognitive distortions, logical cognitive distortions also keep you stuck in the Drama Triangle because they are both irrational and manipulative and therefore delusional.

Perceptual cognitive distortions provide the context, world-view, zeitgeist, and paradigms that determine and control not only what you think is real, but what is even possible. Normally, you do not recognize anything outside your perceptual filtering. For example, supporters for Barak Obama and Hillary Clinton believed both these politicians as well as they themselves were liberals and progressives even though both personally ordered drone bombings that murdered women and children. The world view of these supporters did not allow them to recognize the obvious and absurd contradiction.

All three of these forms of cognitive distortion place you in one of the three roles, persecutor, victim, and rescuer, of the Drama Triangle. Sooner or later you therefore find yourself in all three of them. This chapter is devoted to dealing with emotional cognitive distortions, how each keeps you asleep, dreaming and sleepwalking your way through your life, and how you can wake up out of the limitations of emotional definitions of your identity. The following two chapters will address logical and perceptual cognitive distortions.

Why are Emotional Cognitive Distortions So Important?

Emotional cognitive distortions evoke anxiety, depression or both. They are the most invasive and therefore most destructive of the three types of cognitive distortions. They are fundamental to cognitive behavioral therapy, which has been shown to be effective for the treatment of both anxiety and depression. Principles of cognitive behavioral therapy include:

- How you feel is determined by what you think.

- Change how you think if you want to change how you feel.

A corollary that follows is that it is wise not to believe everything you think. As we shall see in our chapter on perceptual cognitive distortions, IDL finds it wise to not believe much of anything that you think.

You may discover you have a natural resistance to stopping the use of cognitive distortions. This is because they feel true, right, and even fair, even though they are not truthful, right or fair to either yourself or others. Even more problematic, emotional cognitive distortions often feel authentic, which means that you have who you are, your identity, your sense of self, tied up in them. Therefore, to question the legitimacy of a cognitive distortion can feel like an attack on you. Such resistances indicate the extent to which your development is stuck at a mid-prepersonal level, the stage at which who you are is your emotions. By recognizing and neutralizing your emotional cognitive distortions you release who you are from a major fixation and filter that keeps you from advancing up the ladder of the spectrum of consciousness.

“Learned helplessness” is one explanation for certain types of depression. Imagine a cow that gets stuck in a swamp and can’t pull itself out of the mud. It bellows and struggles until it is too tired to continue. It will sleep, then bellow and struggle some more. If no help comes, at some point, it will adapt to its powerlessness and cease futile efforts to escape, efforts that only weaken it. It has learned to be helpless. This is a smart adaptive strategy as long as this cow stays stuck in the mud of the swamp. But what happens if the rancher spots it, comes with a rope and his truck and pulls the cow out of the mud? What has been observed is that some cows will go back into the swamp and become stuck in the mud again. How come? What looks foolish is an adaptational strategy for survival. People can learn that they live longer and even live better if they keep their head down, don’t rock the boat, and adapt to miserable conditions. We can see it in battered spouses who won’t leave an abusive relationship and in combatants that sign up for a second or third tour of combat duty. Such people have adapted to, and perhaps even thrive on, an abusive reality that is deeply lost within the Drama Triangle. We know that people with a pessimistic explanatory style are likely to be both depressed and exhibit learned helplessness. They see negative events as permanent and think, “It will never change.” This is an example of a cognitive distortion called “Jumping to Conclusions” that we will explore below. They also see negative events as personal and think, “It’s my fault.” This is an example of Personalization, another cognitive distortion. People with a pessimistic explanatory style also view their problems as pervasive, thinking “I can’t do anything correctly.” This is an example of another cognitive distortion called Overgeneralization.

Cognitive distortions are false, irrational, delusions that you tell yourself. Whenever you use a one, you are in the Drama Triangle. You use some cognitive distortions to abuse others or yourself, putting you in the role of the Persecutor. You use others to validate your feelings of victimization. Still others are used to rescue you from those feelings. You use cognitive distortions to rescue yourself from some discomfort by telling yourself something that is delusional, such as, “If I eat this chocolate, I’ll feel better.” By doing so, you persecute yourself by keeping yourself stuck in delusions (that eating chocolate will really make you feel better instead of giving you a temporary lift) that turn you into a victim (when you gain those extra pounds you don’t want). If you want to get out of the Drama Triangle, you need to learn to recognize and stop your cognitive distortions.

Cognitive distortions harm your relations with others by misperceiving their intentions and the nature of the relationship. They harm your self-image by distorting your perception of yourself. They turn your waking life into a dream of irrational self-delusion. Cognitive distortions also cause you to misperceive what you experience when you are dreaming when you are asleep at night. This is important because dream experiences can cause you to feel anxious, sad, confused or guilty unnecessarily. Those night-time feelings, consciously forgotten, nevertheless can bleed over into your waking awareness, undercutting your waking efforts to improve yourself. They can bring you down and move you further away from health and inner peace. You are experiencing a cognitive distortion, for example, when you assume a monster in a dream is a threat. Such misperceptions cause you to draw inaccurate conclusions about dreams and dreaming, just as your waking cognitive distortions cause you to draw incorrect conclusions about yourself, people and life. When you identify and eliminate cognitive distortions in your dreams, the twenty percent of your life that you spend dreaming is less likely to be a hindrance to your happiness and growth. When you remember dreams, you are less likely to interpret them through the lenses of cognitive distortions. The result is that you are less likely to draw false conclusions about their value and meaning. This can be very important to your well-being and development, as we shall see.

Much of what is true for cognitive distortions and dreams also applies to near death and mystical experiences. If you have a mind-blowing or mystical experience, and you see it through the irrationality of cognitive distortions, you will misunderstand it, thereby reducing its value for you in your life. This may be a major reason why near death experiences, which are experienced by some seven percent of the population, have not had a greater effect on individuals and society throughout history.

Cognitive distortions are logical fallacies

Every cognitive distortion is a failure in logic. This means that the feeling conclusions you reach about your life do not follow rationally from the assumptions you have made about your experience. Your thoughts are explanatory premises; they generate feeling conclusions. While cognitive distortions are self-destructive ways of thinking, logical fallacies are generally due to either ignorance or a willful desire to misrepresent the facts in order to get the upper hand in some situation. While both cognitive distortions and logical fallacies are delusions, fallacies are mistakes either in your assumptions or the conclusions that you draw from them. They do not so much make you depressed or anxious as keep you stuck in thinking you’re right when you’re wrong, sane when you’re delusional, clear when you’re muddy, and straight when you are as twisted as a barrel full of eels.

Logical fallacies are evidence that you are either not thinking clearly or thinking clearly in an abusive, manipulative, selfish way. To the extent that others represent parts of yourself, to abuse or manipulate someone else is to do damage to the part of yourself that they represent. What does this mean”? Do others represent parts of yourself? Yes, based on at least three lines of reasoning. The first is an inference you can make from your own dreams and the other two you can find from thinking about your everyday experience.

In a dream, if you are chased by a monster and you are scared, who is chasing you? Who is scaring you? Either dream monsters are devil demons beyond your control or they are self-creations or they are both. If they are evil demons, then you are chronically a helpless victim, with no control over your dream world and, by implication, your life. The further implication is that you are a dependent, helpless child in some deep and real sense. If your dream monsters are instead in some way self-creations, then you are chasing yourself and scaring yourself in ways you do not recognize or understand. The implication here is that you are more powerful and more responsible than you literally dream and that you have the ability, by owning your creation of dream threats, to grow into a degree of power, control, and responsibility that you do not yet grasp.

If your dream monsters are self-creations, how much more likely are the trees, houses, roads, clouds, and other people in your dreams to be self-creations? It may be the case that they are objectively real objects from another dimension that you visit in your dreams, but to presume so is to give your power and responsibility away. In that case, you have no part in the creation of the experience, good or bad; it just happened to you. This way of thinking about life tends to keep you in the role of victim in the Drama Triangle. How to get out? By understanding that if you meet someone or something in a dream and you hate it, love it, or ignore it, you are hating, loving, or ignoring those parts of yourself that it represents. This is an example of lucid dreaming, waking up in your dreams; it is part of why IDL is a dream yoga.

However, it may be that your dream events and characters are both; they may be self-creations and external realities. IDL recommends that you always begin by assuming that everything and everyone in a dream is a self-creation, even if it is a revelation, precognition, or a visitation from a deceased relative. This forces you to consider that what you are sure is real is in actuality an externalization of some part of yourself that you are not familiar with. IDL interviews address this question and generally resolve it to your satisfaction by asking during the interviewing sequence, “(Character), you are in ______’s life experience, correct? She/he created you, right? What aspect of _____ do you represent or most closely personify?” The interviewed character may choose to respond by saying, “No! I’m real!” In such a case, it will still in all cases represent or personify some aspect of you. The same is true for your waking experience, which brings us to the second line of reasoning.

When someone makes you angry, or some event, like the prospect of failure, scares you, do you have a choice about how you feel? In normal language and thought, it seems you do not. You may say things like, “You make me feel _____.” “I can’t like you when you treat me like that!” The nature of common language views the actions of others as the source not only of harm and benefits to your physical security, but to your emotions as well. It does so by the use of such structures as, “You make me feel,” or “I have to feel this way when you say ____,” or “I can’t not react when you do ____.” However, notice that if you were to insult someone, you can’t be sure how they will respond. One person will insult you back; another will ignore you; a third may ask you to explain yourself; a fourth may laugh. If there is a choice of responses, the implication is that you get to choose how you feel when things happen to you or when people say or do things to you. Although others can certainly make you feel physical pain by kicking you, no one “makes” you feel love, anger, sadness, or fear. You get to choose what you are going to feel, and how much of it you will feel, in any and every instance.

If this is the case, then others do not make you feel certain things in certain ways. Therefore, their intentions are projections by you; they are not descriptions of the person themselves, unless they agree. For example, I might think, “You are thinking I’m a failure.” “You don’t like me.” Such statements, unless confirmed by you, are projections onto you of my own self-doubt and self-persecution. How do you avoid endless drama in this mirror world? Understand that if you meet someone or some life situation and you hate it, love it, or ignore it, you are hating, loving, or ignoring those parts of yourself that they or it represents. This is an example of lucid living; it is part of why IDL is a dream yoga.

There is a third piece of evidence that is very important. What you know of others, let’s say of me, are the assumptions that you project onto me based on your reading of my words, what others have told you about me, your experiences with other male writers, and your assumptions about who you are and how the world works. You don’t hear me; you hear either validations of who you think you are or challenges to who you think you are. Your culture, history of human contact, ways of thinking and feeling cause you to reach the conclusions you do about who I am and what I mean. But because other people will reach very different conclusions, the implication is that with me, and with life in general, you are mostly shadow-boxing with your own hopes, fears, and expectations. So if you meet me in a dream or your waking life, your response says a great deal about you and very little about me. If you hate me, you are hating those parts of yourself that you represent.

The conclusion is, therefore, that it is both wise and reasonable to assume that both “real” and dream people and objects are first and foremost your self-creations. This is what is meant by saying, “To the extent that others represent parts of yourself, to abuse or manipulate someone else is to do damage to the part of yourself that they represent.” To the extent that others represent parts of yourself, it only makes sense that you treat them as you want to be treated – with respect, clarity, honesty, and fairness. You don’t do good because you should; IDL interviews will demonstrate to your satisfaction that you need to do good to others because you are doing good to yourself, and you deserve nothing less.

As we go through a list of common cognitive distortions, we will indicate how and why each is a logical fallacy. The object of doing so is not only to help you avoid depression and anxiety by breaking your addiction to cognitive distortions, but also to turn you into a clear thinker by learning to recognize and avoid logical fallacies. Logical fallacies damage you by causing you to do two three things, 1) act on wrong or irrational conclusions, 2) think incorrect, untrue, or unhelpful thoughts, and 3) feel self-destructive feelings. For example, if you think, “I failed; therefore, I am a failure,” you are unlikely to try again, which is an example of (not) acting as a result of a wrong and irrational conclusion. It is thinking an incorrect, untrue, and unhelpful thought, because just because you fail at something it does not logically follow that you are a failure. It causes you to feel self-destructive feelings of worthlessness. If you allow your thinking to be determined by your beliefs and emotions, your biases and assumptions will keep you from thinking clearly. As a result, your life happiness and success will be determined by the nature of your delusions.

A number of types of cognitive distortions have been identified and are summarized below. How does each one show up in your life? Your next step will be to learn to substitute true and functional thoughts for each cognitive distortion.

Black or White or Polarized Thinking

Something or someone is all good or all bad:

“I am good and the causes I fight for are noble and right; otherwise, I’m a horrible person and deserve to burn in Hell eternally.”

“You are either trustworthy and my friend or untrustworthy and my enemy.”

How is thinking like this a cognitive distortion? Nothing is all good or all bad. Thinking in terms of extremes is not only a lie you tell yourself; when you see the world in such terms, it becomes a threatening, scary place. No one can be expected to always agree with you and support you, nor should they. Polarized thinking is primitive and regressive. It is associated with early childhood preferences as well as personality disorders, types of mental health disorders in which ambiguity is neither seen nor tolerated.

Polarized thinking keeps you in the Drama Triangle by making everyone, including yourself, into either a persecutor or a rescuer. You, thereby, turn yourself into a victim, condemning yourself to a life of helplessness, hopelessness and powerlessness

Black and white or “all or nothing” thinking is an example of what is often called the “false dilemma” or “excluded middle” logical fallacy. It paints an issue as one between two extremes with no possible room for middle ground or nuance or compromise. It is closely related to the “straw man” fallacy, which essentially presents one side of an argument as being so extreme, that no can agree with it.

Most people habitually experience their dreams through this cognitive distortion. When you see a monster, a fire raging out of control, or you experience falling in your dreams, don’t you normally feel afraid? When you do so, you are engaging in black and white thinking: “This monster is persecuting me and I’m a victim.” “This fire is threatening me and I am a victim.” “I am out of control now that I’m falling and when I hit the ground, I will die.” Isn’t this black or white thinking? How do you know that your perceptions of the monster, fire and falling are true? You don’t. How can you know? IDL teaches you to interview the monster or the fire, and to suspend your assumptions about falling, in order to gain information before drawing wrong or partial conclusions in your dream. Since you are dreaming, you can learn to not react to perceived danger without threatening yourself, whether or not you realize that you are dreaming. Begin by learning to catch and neutralize your cognitive distortions in your waking life; in time, you will start to do the same while you are dreaming!

One lady had a dream in which she loaned her car to two young men. She realized that this was a mistake; they would have fun with the car to see what it would do, and would abuse it. She asked them to return the car keys. They said their boss had them and walked off. She knew they had the keys and made up the “boss” story as an excuse to keep the car. She caught up with them, demanded the keys back, and when they refused, she threw some of her soda in the face of the one she was talking to. She then told them she was calling the cops.

She realized that her natural response was to be confrontational and reactive—to throw soda on someone in her life with whom she was having a conflict. She realized that what the situation needed was cops: the part of herself that could be authoritative and strong, but detached and professional. She was able to handle a current conflict like a “cop” and resolve it: This lady learned a good analogy for handling situations. She could be reactive and metaphorically throw soda in people’s faces when they misbehaved, in an attempt to wake them up, or she could become like a cop: set limits and enforce them.

This is an example of how dreams are working to problem solve while you sleep. However, you generally do not become a co-creator with that process, because you do not take the time or have the tools to bring help to your awareness. When you do, you not only can get immediate support for the specific problem at hand, but also learn more general principles that can move you out of the Drama Triangle and into a life with more inner peace.

Can you spot the black and white cognitive distortion in this dream and in the waking situation it personifies? The dream of the lady and her car are in the role of the Victim while the two young men who borrow it are in the role of the Persecutor. This is black and white thinking in which the dreamer sees parts of herself as persecuting. Notice that when she does so she is tempted to react and turn herself into a persecutor (throwing soda on one of them.) The waking analogy is that she engages in black and white thinking when she views people with whom she has conflict as persecutors. Cognitive therapy teaches you how to substitute a neutral or supportive realistic, rational sentence in the place of your irrational thoughts and your black and white impulsive reactions. Dreams do much the same thing, but in a pictorial, metaphorical way. Instead of providing a rational sentence as a substitute, such as “When I feel attacked I can be assertive instead of aggressive,” as cognitive behavioral therapy teaches, dreams give visual metaphors. In this case, this dreamer was to remember to be a “cop” rather than a “soda thrower.”

Something similar often happens with near-death and mystical experiences. In the small percentage of negative ones, black and white thinking may be causing one to feel threatened by devils, demons and other perceived persecutors. However, the great majority of near-death and mystical experiences are so positive that they are experienced as transformative. How could such mind-expanding experiences be cognitive distortions? First, they may not be. However, if you use black and white thinking in your waking life, it is likely that you will continue to use it to understand a near-death or mystical experience. If you do so, the likely result would be to experience bliss, rapture, unity, heavenly light, tunnels, beings or life reviews, as all “white.” Just as a dream or near-death experience monster would be to some extent a projection or out-picturing of your feelings of being threatened, so a near-death experience angel or mystical experience would be to some extent a projection or out-picturing of your own innate goodness, worth, love and wisdom. While this is undoubtedly a very, very good thing, it is also a distortion in at least two ways. It assumes there is a “you,” you in an experience of complete unity, the distinction between self and other vanishes. So, the experience of there being a permanent, real self may be a cognitive distortion that is commonly projected onto an experience of oneness. Secondly, to believe that such a self, which may itself be a delusion, is all good, is probably unrealistic, not accurate and not helpful, although it can help people who lack acceptance and self-esteem feel loved and cared for. Very positive cognitive distortions can be helpful and make one feel good in the way that falling in love is a positive experience. There is a real but temporary benefit that often ignores a broader reality.

The consequence of an experience of total ‘whiteness” is an unrealistic image of perfection. Because it is unrealistic, it is not integrated. If such an experience cannot be integrated, it doesn’t last. If a mystical experience doesn’t last, it represents a transformational state instead of functioning as a developmental building block. Such total “whiteness” is experienced as savior, messiah and rescuer. It comes to you without you expecting or asking for it, transforming you in ways that you did not expect or ask for. It does not check to see if its “help” is appropriate or not. You are left to figure out how to make sense of it and how to integrate it into your life. Such experiences may not be rescuers any more than they are persecutors. However, if you are using black and white thinking, you are likely to experience them as all black or all white, and that is a cognitive distortion. Understanding or appropriately using mystical experiences is extremely difficult if you have a fundamental misperception of your experience of transcendent unity. If you haven’t already, someday you may have a mystical experience. If you want to experience it most fully and make the most of it, you need to eliminate polarized thinking from your life.

When have you used this cognitive distortion? Write an example…

Now write an antidote for it. For example, here are antidotes for the two examples above:

“I am good and the causes I fight for are nobel and right; otherwise I’m a horrible person and deserve to burn in Hell eternally.”

“I don’t know that the things I believe in are good and right for everyone; if they are sometimes right and I’m wrong, it doesn’t mean either of us are bad people.”

“You are either trustworthy and my friend or untrustworthy and my enemy.”

“Because you’re human I don’t expect you to always be trustworthy. You will be untrustworthy sometimes, just like me.”

Overgeneralization

You exaggerate things.

“I must be a complete loser and failure.”

“I’m always late.”

“You never listen to me.”

Why and how is overgeneralization a cognitive distortion? Exaggerations are never accurate; to believe them or to use them is irrational. When you overgeneralize, you weaken your case, because it’s clear that you are exaggerating. The other person only needs to think of one exception to undercut your entire argument and ignore you: “She can be helpful, so she’s not a complete loser and failure.” “I remember when you were on time, so that’s not true.” “I heard you when you said you wanted me to bring home milk, didn’t I?”

You overgeneralize in your dreams, because you think you are awake, when you are actually asleep and dreaming. You think falling in a dream will kill you, just as it would in real life. The result is that you respond to the experience of falling as if it were a waking threat, which is a cognitive distortion. You’ve overgeneralized. This is the case regardless of the “threat” that you have in a dream. How do you know it’s a threat? Most likely, because you have drawn that conclusion from your waking experience, and you think you’re awake. In post-traumatic stress disorder, people draw this conclusion with their waking mind as a result of an experience of real threat and terror. When they are dreaming, they think they are awake and being threatened again. Every time that this old tape replays in their heads, awake or asleep, they apply the same cognitive distortions to it.

Overgeneralizing keeps you in the Drama Triangle by justifying whatever role you are stuck in at the time: “Because you always interrupt me I don’t have to listen to you.” (i.e., I can stay in the Persecutor role) “Because you don’t love me I’m a victim.” “Because you’re so weak and stupid, I have to rescue you.” When you overgeneralize in your dreams by thinking you are awake when you are asleep, you automatically place all of your dream experiences within the Drama Triangle. All of your dream experiences become a series of cognitive distortions. In the above cited dream about the car keys and throwing soda, the dreamer saw the two young men who wouldn’t give her back her car keys as disrespectful. She overgeneralized when she saw their disrespect as deserving abuse on her part—throwing soda at them. This was an exaggerated response to a perceived threat. It was also an overgeneralization in that she assumed the threat was real when it wasn’t. She was disrespecting herself, since the two men and their actions were self-creations.

A similar thing happens when you have a near-death or mystical experience. Because you are using your waking world view to experience and remember what is happening, you project your generalized, waking assumptions onto them. While much of this is necessary because of the way your perceptual mechanism is physiologically wired, it still doesn’t mean your conclusions are true or accurate. By analogy, just because your senses tell you the sun rises and sets it does not follow that this “real” experience is also true. What it may well mean is that you are necessarily deluding yourself just to function in an illusory, sensory-based reality. The good news is that your delusions and cognitive distortions, as necessary as they may seem to be, can be minimized. They can be reduced, even if they can’t be completely eliminated.

Overgeneralization is a characteristic of many different logical fallacies, such as the “argument from authority.” It says, “because Einstein knows a lot about physics, he must also know a lot about God, religion, philosophy, psychology, relationships and ballet.” Because you respect someone as an authority in area “A,” you assume they are also an authority in areas “C,” “L,” and “Z.” Because Mitt Romney organized the Salt Lake City Olympics and made huge amounts of money while sometimes bankrupting companies, it does not follow that he cares about forty-seven percent of the citizens of the United States, a fact he himself admitted.

Authority can mean either power or knowledge. View the authorities you rely on as resources for decision-making, rather than as providing the final say concerning the issue. When you rely too much on authority, you give your power away to those who may not have earned your trust. Those behind the American invasion of Iraq provide an example of misplaced trust in authority: ““It happens not to be the area where weapons of mass destruction were dispersed. We know where they are. They’re in the area around Tikrit and Baghdad and east, west, south and north somewhat.”—Donald Rumsfeld, May 30, 2003.

Your waking sense of who you are makes decisions for the entirety of yourself, often without consulting other involved and knowledgeable perspectives. This is another common example of overgeneralization of authority. IDL attempts to correct it by bringing the authority of high scoring emerging potentials into your decision making process. This reduces the inherent overgeneralization of power and knowledge to your waking point of view, at the expense of your emerging potentials.

When do you overgeneralize? Write an example…

Now write an antidote for it. For example, here are antidotes for the examples above:

“I must be a complete loser and failure.”

“Because I sometimes fail, it doesn’t mean that I’m a loser and failure.”

“I’m always late.”

“I’m late a lot, but I’m not always late.”

“You never listen to me.”

“You don’t listen to me a lot of the time.”

Filtering

You ignore information and events that disprove your warped beliefs and assumptions.

“Nobody is ever nice to me.”

“I can’t ever do anything right.”

Filtering ignores evidence that does not validate your biases and prejudices. The result is that your perception is distorted and unbalanced. Consequently, you do not see yourself accurately or hear the meanings of others’ words, all the while being sure you do both. Filtering eliminates evidence that you need to change and grow. The result is that you not only stay stuck; you get more stuck over time.

Filtering keeps you in the Drama Triangle by “rescuing” you from objectivity, clarity, evidence, facts and the truth. As a result, you can maintain the righteous judgmentalism of self-persecution and validate staying stuck in the role of the Victim. An excellent example of filtering is the social scripting you went through as a child. You were taught that in order to survive and grow within your family, you had to accept and internalize their cognitive distortions. For example, if you grew up with an alcoholic parent, you had to deal with that reality somehow. Chances are, you distorted reality in one way or another to do so. Your drinking mom or dad really wasn’t sick, or it was all your fault, or you isolated yourself in one way or another. You filtered out options that would be available to children who didn’t have an alcoholic parent. As you grew, your sense of who you were and how you saw your family and the world were all products of the cognitive distortions inherent in your family culture.

You can see from the previous two cognitive distortions, black and white thinking and overgeneralization, that filtering is at work in your dreams. You filter such experiences because of your emotions, your world-view, your life scripting and your biology. The very nature of this filtering is to distort the truth. Consequently, filtering in dreams and mystical experiences is broader than the traditional concept of filtering for waking, cognitive distortions. In the dream of the soda-throwing lady, she filtered out the possibility that these two young men might be aspects of herself or that she was dreaming. It is not merely a matter of filtering out the good so you only see the bad; it is about filtering out reality by imposing your own intervening filters of time, space and identity. People who have had compelling dreams or mystical experiences tend to argue, “The experience was so real, so different from my normal experience that I couldn’t have been filtering anything. It was as if my soul was seeing things without that filtering.” This may indeed be what is happening, or it may be partially what is happening, or it may not be at all what is happening. The most likely and reasonable explanation is that this is partially what is happening: normal filters are dropped during such experiences and you are filtering so much less than you normally do, that you are sure that you are not filtering at all. However, if you read or watch accounts of near-death and mystical experiences and look for evidence of filtering, along with the other cognitive distortions, it is not difficult to find considerable evidence of them.

How can you tell when you are filtering? Unless you first assume that you are filtering, you will never look for it. Therefore, get in the habit of asking yourself, “If I were filtering out something that I would rather not think about, feel or experience right now, what would it be?” The object is not to flood yourself with physical pain, memories of old losses or fears about the future. The object is to continue to filter out what is unhealthy or unnecessary while reducing your filtering for everything else. For example, consider the possibility that some ninety-five percent of the time that you are afraid, worried or anxious that those feelings are either unnecessary or not helpful. What are you filtering out? You are filtering out your peace of mind! Once you see this is the case, you can ask yourself, “Do I need to filter out my peace of mind?” “Is that a helpful decision?” “How much peace of mind do I deserve to experience right now?”

Filtering is an example of a logical fallacy called the “fallacy of exclusion.” You think that some behavior is unique when it’s not or you convince yourself that something is true but only by ignoring evidence that it is not.

When have you used this cognitive distortion? Write an example…

Now write an antidote for it. For example, here are antidotes for the examples above:

“Nobody is ever nice to me.”

“That’s not accurate. Martha smiled at me in the hall and John asked me how I was doing.”

“I can’t ever do anything right.”

“I got to work on time today; that’s something. I returned Max’s phone call. That’s something. So it’s not true that I can’t do anything right.”

Jumping to Conclusions

You assume.

“They didn’t say hi or look at me. They must not like me.”

“I’m going to lose my job because I said I was sick when I wasn’t.”

How is thinking like this a cognitive distortion? Instead of asking questions and getting more information, you make up your mind. If you don’t like ambiguity or uncertainty, you might do this. However, life is ambiguous. Things are uncertain. Getting more information is empowering.

“Mind reading” is a particular type of jumping to conclusions. You know what other people are thinking about you without asking, because you just “know.” You can tell when people don’t like you or are gossiping about you or are ignoring you because you just “know.” What healthy, wise people do is ask themselves, “How do I know this? Can I read minds? Perhaps, I am jumping to conclusions. Perhaps, I need to get more information.”

“Fortune telling” is another subtype of this cognitive distortion that occurs when you “know” what’s going to happen. The second example above is fortune telling: “I’m going to lose my job because I said I was sick when I wasn’t.” How do you know this? Are you psychic? This is an outcome that you fear; you are presenting it to yourself as if your fear is a reality when it is not. It is a possible future outcome. It may or may not happen, and that’s what you tell yourself when you catch yourself fortune telling: “This feeling is about a possible future outcome. It may or may not happen. Other things may happen. I can choose to feel different ways about the future.”

Clearly, your dream experience is mostly about jumping from one conclusion to the next without ever bothering to check to see if you are correct. When you make assumptions, both while dreaming and later, while awake, about the nature of your dream, without first asking questions and gathering information, you are jumping to conclusions. Even if the conclusion is positive, helpful and even transformational, if you didn’t first ask questions and gather information, your conclusions are colored by this cognitive distortion. IDL attempts to counteract this perceptual habit by teaching you to interview dream characters, so that you can gain information that will allow you to draw realistic conclusions about them. Curiously, most people don’t care if they are jumping to conclusions if the conclusion is healing, positive and transformational, such as falling in love or having a mystical experience. Are positive delusions as harmful as negative ones? No. Are they as important as negative ones? Probably not. However, you probably know from bitter experience what the consequences can be about jumping to the conclusion that someone loves you and will make a good partner or that something is a good investment. Even with information, such circumstances are difficult; how much more so are they when you just follow your feelings, intuition and hunches and jump to conclusions?

You keep yourself in the Drama Triangle when you jump to conclusions, because you lack objectivity, since you don’t gather the evidence you need to see the big picture. Consequently, you choose to remain the Victim of your lack of information, feeling unnecessarily or inaccurately attacked, misunderstood or ignored. This is the problem with positive delusions reached by jumping to conclusions. It feels wonderful for a while, but there is often a crash landing that wakes you up and makes you wonder how you let that happen to yourself again. You remain a victim of your misperception; you remain in the Drama Triangle, to the extent that you are victimized by your delusions.

When you jump to conclusions, you are using a logical fallacy called “Begging the Question” or “Circular Argument.” You do this when you repeat a claim, belief or feeling without ever providing support for your assumptions. You repeat the same flawed reasoning over and over again: “I know he loves me because he says he’ll never leave me, that I’m the only one for him, that he’d go crazy if I left him.” People often don’t recognize that they are jumping to conclusions by repeating their beliefs without supplying any evidence: “Gay marriage is just plain wrong.” “Drugs are just bad.” “I can’t believe people eat dog. That’s just plain gross. Why? Because it’s a dog, of course. How could someone eat a dog?” “Obviously, logging causes severe environmental damage. You don’t have to be a scientist to see that; just go out and look at a clear cut field and there it is: no trees.” “I know God exists because I feel him in my heart.”

When have you used this cognitive distortion? Write an example…

Now write an antidote for it. For example, here are antidotes for the examples above:

“They didn’t say hi or look at me. They must not like me.”

“Maybe they are thinking about something else. It may or may not be true that they don’t like me.”

“I’m going to lose my job because I said I was sick when I wasn’t.”

“I don’t know that; I’m just afraid that might happen.”

Catastrophizing

You don’t just assume; you assume the worst.

“My chest hurts! It’s a heart attack! I’m going to die!!”

“I always fail at love. I’m never going to find someone.”

Catastrophizing is not simply an exaggeration or filtering; it takes the worst possible outcome imaginable and treats it like it is a reality, as if that is what will inevitably happen. You do this in an attempt to be prepared for anything, but rather than preparing yourself, you simply scare yourself silly. We commonly do this during nightmares, but we also do it with national emergencies, like 9/11. Most of the time this creates “solutions” that are worse than the nightmare: wars in Iraq and Afghanistan killed more Americans than the terrorist attacks on the Twin Towers did. They did by far more damage to the self-worth of America, both as viewed by others and by Americans, than the original nightmare did.

Catastrophizing can take on the form of powerful, socially-sanctioned myths that serve to “circle the wagons” and create group solidarity, generally around a purpose that serves the narrow interests of one sector of society. For example, viewing Muslims as terrorists and then viewing a few terrorists here and there as a major threat to national security served multiple interests. It served the interests of Israel by making the world less responsive to the legitimate rights and interests of the Palestinians and helping to justify aggression against Arabs. It served the interests of those in the United States, like Dick Cheney, who hoped to exploit Iraq for its oil and for those who stood to make money from U.S. military contracts. The perennial belief in the end of the world, the “mother of all catastrophes,” and its Christian version, “The Second Coming of Christ,” play upon the delusion that “I am special (the anointed, the elect) and live in special times (the end of history).” Believers provide each other with a sense of special life purpose and meaning through the sharing of a common delusion. Problems occur when enough people believe such delusions and act on them. Fears can then become self-fulfilling prophesies.

Catastrophizing keeps you in the Drama Triangle by validating your victim status, leaving you constantly on the lookout not just for persecutors, but for Nazis, the plague and the Antichrist. Extreme, negative delusions are generally accompanied by extremely positive delusions of heaven, mystical rapture, salvation and eternal peace. If there were a cognitive distortion that was the polar opposite of catastrophization, these experiences would be candidates. Catastrophizing gives meaning to empty lives. People who cannot or will not access their life compass may be attracted to larger-than-life social dramas to supply validation, meaning and life purpose. There is a direct correlation between the need for a person to hold catastrophic beliefs and the hollowness they find within themselves.

In the dream dream of the soda-throwing lady, she catastrophized that two guys would wreck her car. However, these were dream guys, wrecking a dream car. Is this something to catastrophize about?

Catastrophizing is an example of a type of logical fallacy called “Non Sequitur,” which is Latin for “it does not follow.” This means that the conclusion does not follow the premises. There is a logical gap between the premises or evidence and the conclusion you draw from it. “He didn’t ask me out; no one is ever going to find me attractive.” ‘Nobody liked my lecture; I’m a failure as a public speaker and teacher.” Chicken Little said, “Something fell on my head, so the sky is falling.”

When have you used this cognitive distortion? Write an example…

Now write an antidote for it. For example, here are antidotes for the examples above:

“My chest hurts! It’s a heart attack! I’m going to die!!”

“My chest hurting could mean a lot of things. I’ll get it checked out before I think the worst.”

“I always fail at love. I’m never going to find someone.”

“You’ve gotta kiss lot of frogs before you find a prince.”

Personalization

Whatever happens, it’s all about you.

“She looks angry. It must be something I did.”

“This patient is getting sicker. I must be doing something wrong.

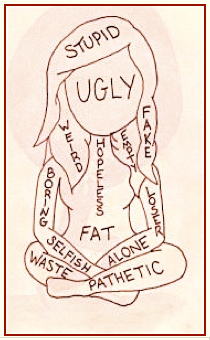

Personalization is an indicator of a person who thinks emotionally rather than rationally. One of the most destructive cognitive distortions, personalization prevents the development of empathy toward others and compassion toward yourself. Sometimes referred to as “adolescent girl syndrome,” personalization is painfully exaggerated self-consciousness. It is common in adolescence, when we are uncertain about who we are and are trying to find ourselves, but even then, it is neither normal nor healthy. When you personalize, you assume that everything that others say must be about you. That is grandiose, narcissistic and egotistical. It’s also not true. Most of what people do or say to you or about you is a reflection of their own beliefs, thoughts and values, not yours. If you didn’t exist, people would pretty much be saying and doing the same things. The truth is that you just aren’t that important to most people, most of the time, because they don’t hear you through the buzz of their self-talk. They don’t see you through the mental images they project onto you; they don’t feel you through the tide of feelings that run through them. Even when they are directly speaking to you, most of what they say is habitual and routine, even if they think they are being spontaneous. If others are critical toward you or about you, it is because they are normally critical of others and themselves; if they are friendly, its is because they are normally friendly; if they seem distant and uncaring, it is because they are normally distant and uncaring. A good rule of thumb is that ninety percent of what people say, even when they are speaking directly to you, is about themselves and not about you. They are reading off a script they learned when they were twenty, twelve or five. Your role is that of a cameo performance in the staging of their life script; whatever you say, whatever you do, will be woven into the predestined plot that they have going on inside their head. You don’t make people think or feel much of anything. They get to choose how they are going to think and what they are going to feel. You are just not the center of anyone’s universe. Even in romantic love, when you are the object of someone’s adoration, that love is primarily directed at who your partner thinks you are and needs you to be rather than at you. If you hadn’t been born, it’s a good bet that your parents would have treated other children pretty much the same way they treated you. They didn’t act the way they did toward you because you were good or bad, happy or sad, smart or dumb. They acted the way they routinely act toward children in such circumstances; you just happened to be the one around at that moment. When you personalize, you create two problems where there was only one. The first problem is that the other person is on automatic pilot and not listening to you. The second problem is that you make their sleep-walking and sleep-talking to be about you. You can’t help others to wake up as long as you are focused on imaginary problem number two.

Dream perception is all about personalization. Notice that in the dream of the soda-throwing lady, she made one assumption after another about the actions and motivations of others without stopping to examine the situation further. She assumed the dream actions of others were about her and her property. She didn’t stop and think, “Maybe this is about them and doesn’t have anything to do with me!” Very rarely, if ever, do people think about dreams in this way. Do you ever stop in a dream and look at it from the point of view of another character? If another character gives you a piece of advice in a dream or tells you what to do or not do, who is giving you that advice? Isn’t it probably a part of yourself that has its own perspective, different from your own? Dream personalization creates the same problems that waking personalization does. You assume that things are about you that aren’t about you at all. You might ask, “If I created the dream, how could anything in the dream not be about me?” The difference is this: if you don’t realize you’re creating the dream, you are very likely to feel threatened or get defensive and get stuck in personalization. When you recognize you created the dream, you no longer take it personally because there is no ‘other’ that is threatening you.

Personalization keeps you in the Drama Triangle by turning life into a tragedy in which you are the lead actor. You have to rescue yourself from the imagined persecution of others. But what if others aren’t persecuting you but only the part of themselves that you represent? While that awareness may not wash away the real damage that their actions can cause, it can keep you from compounding the hurt by taking it personally.

Near-death and other mystical experiences provide excellent examples of this cognitive distortion. People come away from them with a transformed sense of who they are. The experience was about them—about the truth of who they are. However, was the experience about them? How do they know? Maybe it wasn’t about them at all. Perhaps, that was the entire point of the experience—to teach them that life is not about them—and they missed the point. How would they know if they personalized the experience?

Personalization is a curious type of ad hominem logical fallacy. Meaning “to the man,” ad hominem usually refers to attempts to undercut an argument by destroying the reputation of the speaker. I can’t win on evidence or logic, so I will attempt to convince people that you are untrustworthy. The validity of an argument has nothing to do with the character of the person who presents it. In personalization, you assume other people are attacking you instead of evidence or logic. Or, if they attack your evidence or logic, you take it as an ad hominem attack on yourself.

When have you used this cognitive distortion? Write an example…

Now write an antidote for it. Here are possible antidotes for the examples above:

“She looks angry. It must be something I did.”

“Maybe she’s having a bad hair day.”

“This patient is getting sicker. I must be doing something wrong.”

“Maybe I better get more information before I assume this is about me.”

Control Fallacy

There are two types of control fallacies. The fallacy of external control says you are a victim of circumstances beyond your control. Here is an example:

“I can’t help it if the quality of the work is poor: my boss demanded I work overtime on it.”

The fallacy of internal control says you are responsible for other people’s feelings and happiness. Here is an example:

“Why aren’t you happy? Is it because of something I did?”

The first type of control fallacy ignores the part that you play in how you think or feel, or in what happens to you. The second type ascribes too much responsibility and power to you over the lives of others. You are not without responsibility, but you’re not responsible for everyone and everything, either. If you take too much responsibility in life, then you think you somehow are magically responsible for children dying in Africa or for global warming. If you take too little responsibility in life, you think that you have no responsibility for children dying in Africa or for global warming. This poses a constant dilemma of imbalance: you are either erring by taking too much responsibility or too little. It will help if you steer clear of broad generalizations and philosophies that tend to tilt the problem of control too far in one direction or another. For example, the doctrine of karma tends to cause people to take so much responsibility that they do not fight for justice and accept blatant discrimination. Capitalism takes too little responsibility by justifying selfishness, thus encouraging and validating exploitation. The belief that something is “God’s will”, or that “everything is in divine order, is a way of avoiding responsibility and errs on the external control side of this cognitive distortion. Socialism and communism, by making the state responsible for the health, prosperity and happiness of citizens, takes too much responsibility, erring on the internal control side.

Whenever you feel out of control in a dream, you are probably using the external control aspect of this cognitive distortion. Whenever you blame yourself for dream events, you are probably trapped in the internal control aspect of this cognitive distortion. If you feel there is something you did or can do, like meditating, joining a monastery, loving or choosing a life of selfless service, that will make near-death and other mystical experiences more likely, you are probably experiencing the internal control aspect of this cognitive distortion. If you beat yourself up because the experience went away, because you don’t remember more of it or because you didn’t stay, instead of returning to your crummy life, then you also are probably experiencing the internal control aspect of this cognitive distortion. However, many people return from such experiences convinced that they have seen God and heaven and that they know that they not only will survive death, but that they have an immortal soul. These people are probably victims of projecting too much external control onto their experience. It is so overwhelmingly transformational, so totally “other,” that they probably give the experience itself too much responsibility for its reality, meaning, significance and value. They disown the part that their consciousness plays in creating it. When applied to near-death and other mystical experiences, the control fallacy produces results that are not only unhelpful but positively toxic. People sometimes so try to hold on to and control the experience, that they seek validation for the experience by convincing others that they not only experienced their truth, but a universal truth. This is another cognitive distortion we have already looked at: overgeneralization. What is true for me is true for you. Out of a desire to control and maintain the experience, one spreads the Good Word, and a cult or religion gets founded. This is toxic, because it teaches people to believe your truth rather than teaching them how to find their own. Consequently, this perspective places you fundamentally in the rescuing position of the Drama Triangle, and that is disempowering.

The control fallacy keeps you in the Drama Triangle by defining you either as a perpetual victim or as a savior. If there is too much external control, you are a victim. If there is too much internal control, you are a savior. Neither is true or helpful. When have you used this cognitive distortion? Write an example…

Now write an antidote for it. For example, here are antidotes for the examples above:

“I can’t help it if the quality of the work is poor: my boss demanded I work overtime on it.”

“It’s partially my responsibility that my work is not up to my usual standards.”

“Why aren’t you happy? Is it because of something I did?”

“Why aren’t you happy?”

Fallacy of Fairness

Life should be fair.

“That’s not fair!”

When you insist that life must be fair, you are assuming that your rules for life are the universe’s rules. How likely is that? It is more likely that you have a set of expectations that are more important to you than listening to life and growing. However, you want to feel that you are on the right track, so you look for some sort of validation, either by believing you are doing “God’s will” or by seeking social validation by making money, collecting status symbols, such as houses and cars, or having people laugh at your jokes. The problem with this cognitive distortion is similar to that with control fallacy. Just as you can insist on too much control or give too much control away, you have to find your own balance with fairness. You have to learn to thread the needle between life needing to be fair, on the one hand, and life being unfair, on the other. The reality is that life is neither fair nor unfair. That’s your projection onto life. You can see this if you think about the sun. Does it care whether you get sunburned or not? Does it send out flares because human actions make it mad? If you get too much sun, bad things happen. If you get too little sun, bad things happen. It’s not about the sun being fair; the sun is remarkably consistent at doing what it does; its actions are not about you. It is neither fair nor unfair. Thus, so is most of life. Humans, for the most part, are more interested in getting their needs met than in being fair. If being fair helps them get their needs met, they will be fair. If proclaiming the importance of fairness will get you to play by the rules in a way that gives them an advantage, then advocating fairness, rather than being fair, is what is done. Think about times when people have told you to “play fair” or “be fair,” or told you, “That’s not fair!” What were they doing? They were trying to get their needs met and felt that you were getting yours met at their expense. You would be wise to stop thinking in terms of fairness and unfairness. Such definitions are arbitrary and change based on convenience and self-interest. It is much wiser to think in terms of avoidance of cognitive distortions and the Drama Triangle while cultivating your ability to deeply listen to your emerging potentials.

One of the major reasons you don’t pay more attention to your dreams is that there isn’t much about them that’s fair. They don’t and won’t consistently play by your rules. They will often seem to agree to your rules and then veer off in a way that causes you to feel misled, betrayed or cheated. No wonder you don’t trust them. Think about the dream of the soda-throwing lady. Was anyone playing by her rules? However, the problem is not that your dreams don’t play by your rules; the problem is that you haven’t learned how to play by their rules. If you did, there would no longer be an issue of fairness, because this is not a value or standard that is commonly expressed by interviewed dream characters. Consequently, you wouldn’t let this cognitive distortion get in your way regarding dreaming. Interview your dream characters regularly and you will soon recognize that your dreams transcend issues of fairness. They transcend and include both your sense of fairness and your warped sense of unfairness.

Many near-death and mystical experiences undercut this cognitive distortion. People come away with a conviction that their definition of fairness is totally inappropriate and ridiculously narrow. Consequently, these experiences, like IDL interviewing, tend to be an excellent antidote for this cognitive distortion.

The fallacy of fairness keeps you in the Drama Triangle, by your wanting the world to rescue you by treating you the way you think you deserve to be treated. If it doesn’t do so, it’s persecuting you, and you have earned the right to pout, sulk and blame. In near-death and mystical experiences of unity, you are treated way better than you could possibly deserve, in that you are likely to experience oneness, wisdom and compassion, regardless of your level of development, your treatment of others or your own self-image. Therefore, issues of fairness tend to be transcended, and with it, you gain some freedom from aspects of the Drama Triangle.

The fallacy of fairness is an example of a logical fallacy called “hasty generalization.” It involves mistaking a small incidence (something that happens to you) for reality. Your partner cheats on you and you conclude that’s not fair, which leads to you justifying feelings of hurt, anger and fear. But if you no longer draw the conclusion of fairness, or the lack of it, then other emotional reactions open up. You could laugh at the situation. You could be thankful she’s getting her needs met. You could remain an adult and ask them what’s going on instead of jumping to conclusions.

When have you used this cognitive distortion? Write an example…

Now write an antidote for it. For example, here are antidotes for the example above:

“That’s not fair!”

“There are a lot of things in life that don’t live up to my expectations. I can learn to deal with that.”

Blaming

Somebody’s always to blame! It couldn’t be me, could it?

“Stop making me feel bad about myself!”

“I would be happy if it weren’t for…”

Blaming is a cognitive distortion, because it is irrational. Taking responsibility is one thing, but blaming is another. Is it rational to blame yourself? If others represent those aspects of yourself that you project onto them, then to blame someone else is to persecute the parts of yourself that they represent. Is that what you want to do? If someone hurts you, is it wise for you to then turn around and hurt yourself by blaming? In addition, blaming is regressive. It’s behavior you mastered when you were five. When you blame, you are demonstrating your proficiency at five-year-old behavior. That’s fine, but what about your ability to act like an adult? Can you do that? It’s easy to be mature, competent, friendly and responsible when people are nice to you and when things are going well, but what about those times when people treat you badly or you are under pressure? Character is defined by how you act at such times, not by who you are when everything is either wonderful or cruising along on automatic. When you blame, you give somebody or something power over how you feel and what you can or cannot do. It’s their fault; therefore, you are claiming you are powerless in the face of God’s will, the government’s power or your boss’s policies. Is that smart? Is it rational?

If you blame others or yourself during your waking life, this routinely boomerangs into characters or events persecuting you in your dreams. This is because your dreams mirror your waking problem solving strategies. The soda-throwing lady sometimes blames herself and others in her waking life; is it any wonder that she manufactures persecutors in her dreams? While reducing blaming will reduce dream persecution, it won’t eliminate it, because there are other reasons for apparent dream persecution besides waking blaming. However, if you blame in your waking life, you are thereby incubating dreams that reflect that theme. They will haunt you and unravel the progress you’ve made in your waking life, whether or not you remember them. While blaming others and yourself may feel justified and useful to you, you will pay the price tonight when you go to sleep.

This is another cognitive distortion that tends to be neutralized by near-death and mystical experiences. Because of the experience of unconditional compassion, love and acceptance that is common with these experiences, blame is often replaced by a deep sense of forgiveness. This is itself problematic, because from the perspective of life itself, it may well be that there is no one to forgive and nothing to forgive. However, anything that moves you out of self-persecution is a huge improvement, even if it is later seen to be a delusion.

Blaming keeps you in the Drama Triangle by making you the victim in your own mind. You make yourself powerless, validating feelings of helplessness, hopelessness and depression. Is this what you want? Is this smart? Do you have the ability to think like an adult and resist regression to a five-year-old’s level? Blaming is another example of the ad hominem logical fallacy, whether directed toward others or toward yourself. In this fallacy, instead of examining the thinking that caused you or someone else to make a mistake, you attack yourself or that other person. Blaming always feels justified but looked at objectively, it’s always a self-defeating and stupid reaction to life’s challenges.

When do you blame yourself? Others? Write an example of each…

Now write an antidote for each. For example, here are antidotes for the examples above:

“Stop making me feel bad about myself!”

“You don’t have the power to make me feel bad about myself unless I give it to you. Why would I want to do that?”

“I would be happy if it weren’t for…”

“I can choose to be happy independently of what happens or what other people say or do. It’s not always easy, but I can do it.”

“Should-ing” on Yourself:

Self-persecution as a lifestyle:

“They shouldn’t be doing/saying that…”

“I ought to be better/more professional, happier, wealthier, better-looking…”

“I must exercise more. I shouldn’t be so lazy.”

“I should be loving toward everyone.”

Thinking or talking in terms of “shoulds,” “musts,” or “oughts” is a cognitive distortion, because it is based on the belief that shame, guilt and abuse are effective and worthwhile motivational tools. In the short term, they are effective, in that they get others to discipline themselves so that you don’t have to. If you can brainwash a child, spouse or employee into doing what you want them to do because they should, your life is much simpler. However, you are generating compliance based on fear. That reflects poorly on you and produces resistance in healthy children, spouses, workers and citizens. Shoulding is also a cognitive distortion, because it is dishonest and manipulative. If you love someone, you don’t attempt to scare them or make them feel guilty. For example, some parents who love their children use fear and guilt because they lack patience, tools or self-discipline. Other parents are selfish and use guilt to socialize their child into behaving.

People who have near-death or other mystical experiences often fall into this cognitive distortion. They think they “should” feel more like they did during the experience. They think they “should” do more to keep it alive. This distortion may explain some of the driving force toward proselytization that many people who have near-death experiences feel.

When you use should, must or ought, you keep yourself in the role of the Persecutor in the Drama Triangle. You are persecuting yourself. Some people don’t look at their dreams, because they bring up “shoulds:” “I should be more in control;” “If I were really healthy, I wouldn’t have such irrational and scary dreams.” Before you can look at your dreams in an objective, productive way, you need to outgrow this cognitive distortion.

In addition to being another example of the ad hominem logical fallacy, “should-ing” demonstrates another, called “moral equivalency.” It equates two moral issues that are, in fact, different. The first is your unrealistic expectation for yourself or for others, based on what you have been taught to expect or want to have happen. The second is reality. For example, if you set for yourself the moral expectation not to be lazy, then you will “should” on yourself whenever you don’t exercise “enough.” But since “enough” is always more than what you are doing, you feel justified in constantly beating yourself up. The only way out of this moral fallacy is to identify and give up your unrealistic expectations for yourself and others.

The good news about this cognitive distortion is that it is relatively easy to stop. All you have to do is stop using should, must and ought when you speak. Enlist your children or co-workers to point it out to you when you do it. If you eliminate it from your speech, you will find that you stop talking to yourself, that is, thinking, in those warped, dysfunctional terms. Good alternatives to “should,” “must,” and “ought” are not difficult to find. Look at the examples below.

When have you used “should-ing” on yourself? Write an example…

Now write an antidote for it. For example, here are antidotes for the examples above:

“They shouldn’t be doing/saying that…”

“I think it would be better if they didn’t do/say that…”

“I ought to be better/more professional, happier, wealthier, better looking…”

“I think it would be better if I were…”

“I must exercise more. I shouldn’t be so lazy.”

“I need to exercise more. It would be better if I wasn’t so lazy.”

“I should be loving toward everyone.”

“I would like to be more loving toward everyone.”

Emotional Reasoning

“I feel it, therefore it must be true.”

“Because this feels stupid and boring, it must be stupid and boring.”

This cognitive distortion is the exact opposite of what cognitive behavioral therapy teaches. It says that how you feel determines what you think. Cognitive behavioral therapy says that if you want to change how you feel, you need to change how you think. This distortion says that you can’t change how you think, because your feelings are real. The point is not that your feeling are unreal, but that they make poor masters of the house of your consciousness.

Emotional reasoning is another example of a “living fossil,” like an ancient fish discovered still living in the ocean. It is a way of being that was perfectly normal and common during an earlier era of your development. You have created conditions that have allowed it not only to survive, but to flourish in a time when your needs and challenges have evolved far past it. As a child, your feelings made something real or unreal, good or bad. You didn’t have any choice, because you hadn’t yet developed the ability to think about your feelings. You probably know adults who are quite smart and capable, yet still don’t think about their feelings. Therefore, their preferences define their reality. What they like is good, true and real, while what they don’t like is bad, false and illusory. Consequently, their life is an emotional roller coaster in which they constantly move toward what they like and away from that which they dislike, even when what they like is killing them, and what they dislike is what they need.

The Hindus have a famous metaphor about this. Your body is a chariot, you are the driver and your emotions are the horses. If you let the horses guide the chariot, you may go over a cliff or go nowhere at all. In any case, you are in for a bumpy ride. You need your horses, but not for them to be in charge. This analogy roughly correlates with cognitive behavioral therapy, which puts reason in charge of the chariot. Hinduism improves on this by having Krishna as a guide in the chariot—a metaphor for your life compass. Just using your reason to stop your cognitive distortions is very good, but it is not enough. You need the direction of your life compass.

When you dream, your reality is largely determined by how you feel. If you are threatened or scared, certain things happen in the dream. The lady throws soda. If you stay calm and non-reactive, other things happen in the dream. This is a vast improvement, but it is not enough, because “thinking happy thoughts” and being an optimist, can still be a cognitive distortion. Your emotions are your horses. Let them take you where your life compass tells you to direct them, whether you are awake, dreaming or having a mystical experience. Don’t allow them to choose where you are going to go, unless you like being taken over a cliff every now and then.

In near-death and mystical experiences, extraordinarily positive feelings do determine not only what you think but who you are. It’s as if the horses pulling your chariot grew wings and turned into Pegasus or, more bizarrely, Krishna grew wings and started pulling your chariot. Are such feelings cognitive distortions? Are they to be trusted? If they are cognitive distortions, they are extremely healthy, beneficial ones. Yes, it is important to listen to them and trust them. The challenge is to integrate those feelings in a way that they do not swamp your ability to think. No matter how lofty a feeling is, it takes reason to channel it into a way that is useful and makes a difference.

Whenever you attempt to win an argument inside your head or with someone else by getting angry, “hurt,” excited, defensive or funny, rather than focusing the quality of the reasoning or the evidence, you are using the logical fallacy of “emotional appeal.” It is either an implicit threat: “Bad things will happen if you don’t agree with me.” (I’ll blame you, throw a fit, ignore you, you’ll hurt my feelings and then you’ll be sorry, I’ll withdraw my financial support, cut you off sexually, etc.) It can also be an implicit promise: “Good things will happen if you play along with me. I’ll make you feel good and forget about your problems. I’ll make your life seem easier.” These are promises that you know the other person can’t fulfill because happiness is an inside job, but you will forget that for now because you want to feel good, and they make you feel good.

You use emotional appeals because they often work. There have been times in your life when you have been able make people scared and act out of their fear; you have been able to make people relax, suspend their disbelief and trust you. You know you can manipulate people into not thinking and instead trusting the feelings that you evoke in them. However, you also know that this is dishonest. It is about their weakness and inability to see through your phoniness rather than due to any real strength, other than a cultivated, narcissistic manipulativeness on your part. At some point in life, you and everyone else has to learn how to recognize emotional appeals them and counteract them; no one is born with this ability. Identifying and counteracting emotional appeals is not a skill most people learn because your parents, teachers, as well as product manufacturers and politicians know that keeping you ignorant and unskilled in this area increases their power and control. They get more of what they want out of you, at your expense. Consequently, you fall victim again and again to this logical fallacy throughout your life, not just expressed by others, but also expressed by you toward yourself.

How does emotional reasoning keep you in the Drama Triangle?

When have you used this cognitive distortion? Write an example…

Now write an antidote for it. For example, here are antidotes for the examples above:

“Because this feels stupid and boring it must be stupid and boring.”

“Just because I have strong feelings toward something or someone, that doesn’t make them true, right or good.”

Fallacy of Change, or

“Waiting for Santa Claus”

Your happiness depends on change, in others, yourself or both.

“I can’t be happy unless you change.”

“I can’t be happy until you change.”

“I can’t be happy until I change.”

This a cognitive distortion because it puts happiness in a future that does not yet exist and perhaps never will. That makes it impossible to be happy now, which is untrue, since you can choose to be happy now, regardless of how things turn out in the future. “Waiting for Santa Claus” gives your power away to someone else or to the future. Santa Claus can make you happy, but since he’s not here yet, you can’t be happy. Without the power to make yourself happy, you are helpless and hopeless, stuck in the role of the Victim in the Drama Triangle. Sometimes people use this cognitive distortion when they are afraid of their power; perhaps, if they had it, they would misuse it; perhaps, they would be expected to perform, and they are certain they would fail. “Santa Claus” may be a job, Prince Charming, a move, a winning lottery ticket or a promotion. It could be the acknowledgement of one’s children for the sacrifices you made raising them. It could be a return to health. In any case, when you use this cognitive distortion, you are making excuses for staying stuck. If you don’t want to change or don’t see how you can, that is one thing; lying to yourself about it is entirely another.

A lot of people approach dreaming as if they were waiting for Santa Claus. They don’t like their normal, irrational, “unfair” dreams, and so they divide them into two categories, “mundane” or “day residue” dreams and “big,” “spiritual,” or “divinely inspired” dreams. Then, they spend their time ignoring the first and hoping for the second, rather like the skeleton lady in the picture above, ignoring opportunities for love and forever hoping “true,” “pure,” or “real” love will come her way. This classical distinction of dreams and dreaming made in many cultures is a cognitive distortion.